BY REBECCA FISSEHA

What’s the sound of a fistful of zero-defect coffee beans dancing in a hot tin pan? It’s a crackle and a hiss as they brown and release their smoky oil, and the soundscape of “Bu’na: The Soul of Coffee” — Toronto’s only café to welcome its patrons with a waft of frankincense at the door and offer freshly hand-roasted, jebena-brewed Ethiopian coffee all day.

The café, owned by Chris Rampen and his wife, Nunu, celebrated its soft opening in January. When I first met the pair, the café was still under construction. But being someone who always forgets how much she adores the traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony until she is re-experiencing it — months if not years apart — I kept in touch and peeked out the window of the Queen West streetcar every time I rode by the storefront.

Toronto experienced an indie coffee shop craze a few years ago, and the enthusiasm shows no sign of abating. As Chris says, “The Toronto coffee world is very saturated. So we’re hoping this creates an experience you would go out of your way to visit.”

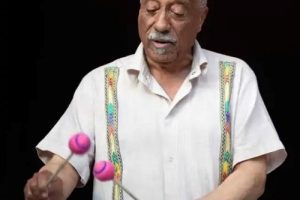

While Nunu alternates overseeing the work from behind the counter and computer, I sit down for a chat with Chris under the hand-painted map of Ethiopia showing the official Ethiopian Commodity Exchange coffee-growing regions. Meanwhile, one of Bu’na’s jebenistas, Helen, roasts a fresh batch of coffee: the first step of preparing ye-jebena buna — coffee prepared the traditional Ethiopian way — just for me.

“A very sexy, lovely coffee pot,” is how Chris describes the jebena: wide-bottomed, thin-necked, long-spouted, and made out of Ethiopian clay. The traditional pot is featured throughout the store like a visual refrain.

“The jebena is a brilliant thing,” Chris says. Rightly so, for if buna is the soul of Ethiopia, then the jebena is the soul of Ethiopian coffee. “Westerners have figured out that the ideal coffee-brewing temperature is about 94 degrees Celsius,” he adds, and notes that the jebena starts to steam right when it reaches 94.

Helen comes over bearing the long-handled, crackling, hot roasting tin and gives it a shake, releasing smoke infused with the aroma of the gleaming dark coffee beans within. We guide the smoke to our faces with our hands and inhale deeply. This, my favorite part of the ceremony, is always over too soon. But I’m looking forward to fresh jebena buna.

Chris’ Ethiopian coffee apprenticeship goes back 20 years, over which time he has developed a deep respect for the culture. “Ethiopians got it right,” he says, a phrase he is fond of emphasizing. “They came up with the best way to experience coffee, and we wanted to offer that experience properly to Torontonians.”

“A lot of people don’t even know what a green coffee bean looks like,” adds Chris. Nor, apparently, that Ethiopia is the birthplace of coffee. Part of the shop’s mission, therefore, is to educate patrons about the oldest and most predominant coffee culture in the world. “People do not associate coffee with Ethiopia necessarily. If there is a coffee culture in the world, it’s Ethiopia.”

Helen delivers my cup of sweetened buna. Like the customers Chris speaks of, who have been conditioned to drink “rancid” coffee by the North American coffee industry, I too am momentarily stunned by how luxuriously delicious this fresh coffee is. I delight in the gourmet experience.

By now, Yirgacheffe and Sidamo are familiar names to coffee aficionados, but not even most Ethiopians will have heard of Benchmaji, about 700 km from Jimma. It is the oldest coffee-growing region in the world and home to the Benchmaji Farmers Co-Operative Union, with a membership of some 65 co-ops and 26,000+ small farmers.

“It’ll take a while, but I know one day people will know about it. The real coffee is in Benchmaji.” Chris Rampen.

As Nunu tells it, when she and Chris began to pursue opening a café six years ago, they knew they wanted to source beans directly from Ethiopian farmers. Fortunately, they discovered that a family friend of Nunu’s had contacts to farmers in Benchmaji. Nunu and Chris traveled to Addis to meet with the Benchmaji farmers’ representative, who in turn took them to meet the farmers and see the harvest.

“It’s unspeakably beautiful,” Nunu says of the two-day drive from the capital to Benchmaji. “I’ve never seen any place like that. It’s nonstop evergreen mountains, very rural.

“We saw how they harvest,” she adds, and “that they don’t give the coffee anything. It is just grown naturally in deep forest. Only when it’s ready, they go in with their baskets and pick it. It’s fragrant, fertile country.”

Despite its purity, much of the Benchmaji harvest languishes in the Buna Board storehouse in Addis Ababa, so the farmers were happy when Chris proposed how they could introduce their coffee to the world.

“No one knows about it; only a few German and Swedish traders buy from them in small quantities. So, Chris said we have to introduce this coffee. It’s good for us and good for them,” Nunu says. “I feel that we haven’t done enough for them yet…It’ll take a while, but I know one day people will know about it. The real coffee is in Benchmaji.”

In addition to the Benchmaji co-op partnership, Chris says Bu’na is currently developing three more with farmers in Tefi, Yirgacheffe and Sidamo. “These partnerships are aimed at branding Ethiopian coffee in a new way. We are collaborating with the co-ops to bring a modern marketing approach — from logo design, to website and social-media development.”

Bu’na is also working on a new distribution model where it would essentially function as a warehouse for the co-ops, giving them the ability to sell individual bags of coffee to North American specialty roasters that don’t have the resources or desire to buy full containers.

And so far, business at Bu’na has been fantastic. Although some customers come across town for the unique experience, most of the café’s regulars are neighborhood locals who get their coffee to go. One such customer is Thulani, a banker from South Africa who has been coming since the shop opened. He usually orders the jebena double. “This place is unique. It’s different from West Queen’s arty-farty vibe. The music, the staff, it feels more like home,” he says. “You know what you’re drinking, where it’s coming from, how it’s made.” In addition to jebena, Bu’na also offers the traditional coffee shop brews — Americanos, macchiatos, chai lattes and so on — all of which are prepared with freshly roasted beans, of course.

Customers who happen to come by in the early afternoon and have time to spare can even enjoy a half-hour demo on how to hand-roast Ethiopian-style and brew with jebena. “We do a little cupping class at the end so they can taste the difference,” Chris says. He also teaches, by invitation, a “coffee sommelier” course, partly geared at cultivating business with high-end restaurants. Chris calls it “a micro-advertisement for organic, beyond fair trade coffee.”

And yet the jebena — and the shop staff’s skill at pouring it — remains the most effective advertisement for Ethiopian coffee. The stove at Bu’na regularly rotates through two or three of the brewing pots, and hand-roasting is a constant. No matter the time of day, a multi-sensual experience awaits every customer who walks in the door for jebena buna: a phrase that, judging by the online reviews of the store, will soon become part of Torontonians’ common lingo.

Source: www.selamtamagazine.com