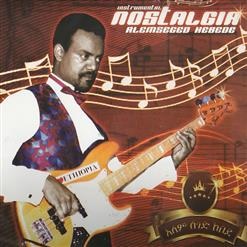

There’s yet to be a genre from Ethiopia that has risen in the world’s music scene the way that Ethiopian jazz had in the first half of the 20th century. Sampled across many genres and artists, the unique sorrowful yet joyful and even mystical sounds that came from Ethiopia at this time became a worldwide phenomenon. This, however, is a story about one among many, who was part of this cultural phenomenon and continues to be today—my beloved uncle, Alemseged Kebede.

Alemseged is currently the bassist for Feedel Band, a modern Washington D.C. based, Ethio-Jazz band that actively travels throughout North America preforming various gigs. Alemseged’s career however stretches back to his high school days when he first began teaching himself how to play the guitar by imitating none other than his older brother Meseretab Kebede.

Alemseged recalls, “When my brother and his friends would get together and play music, and I’d happen to be there in the moment, I’d see how he played. At the time, he actually didn’t even let me touch his guitar for fear that I’d damage it somehow.”

Despite this impediment, Alemseged’s eagerness to learn wasn’t curbed. “When my brother and his friends weren’t around, I’d get his guitar and attempt to copy some of the things I just saw them play. That’s how I got my start,” Alemseged says.

Like in any sibling dynamic, it’s a natural desire to be like one’s big brother or sister. But this was coupled with Alemseged’s relentlessness to learn this new, and at the time rare, skill.

He tells me, “As soon as I’d come home from school, the first thing I’d do was practice the guitar.”

Since Meseretab was also a musician in his own right, primarily with Dadimos band, he was friends with those who were involved in the bourgeoning music industry at the time. Alemseged mentioned David Kassa, who was a guitarist of Dahlak band, and close friends with Meseretab. David would occasionally come over and share tips with Meseretab; but little did they know young Alem was taking mental notes he’d later incorporate in his daily practice sessions.

This soon led to more formal training when a music program opened in Alem’s kebele: “for 3 months, about the entirety of winter, I had the opportunity to learn the basics of music (in a more formal way).”

He says “My instructors thought I made a good student and encouraged me to go on, but the program mostly consisted of piano and cultural instruments—not really guitar. But I was able to get a baseline understanding of reading notes and classical music structures and so on. Once school began, however, I returned to just playing my guitar at home.”

This didn’t last too long before Alem got his first opportunity to perform for a live audience. Alem says, “I met Yosef Legesse, who was a drummer and a friend of my brother’s, was well acquainted with the social goings-on of multiple cities. He told me about an event happening in Piazza where I’d have an opportunity to perform. There, I saw so many different groups.”

Alem continues, “At the time Ayalew Mesfin didn’t have a bass player—and musicians really just wanted people who had some semblance of an ability to play modern instruments like the guitar. So, while I was in Piazza, they handed me a bass guitar and I riffed here and there, played what I’d known up to that point. They immediately thought I knew how to play—I was surprised because I saw myself just starting off, not really knowing too much. But regardless, they told me we’d practice together, and that I’d go with them to accompany Ayalew Mesfin to Harar.”

He jokingly recalls, “After that my ego was enormous. Even my brother couldn’t believe what I’d just done. It was after this moment my brother and I began playing together at home and in public whenever we could.”

At this point in his career, Alem was spending a lot of his time bouncing between different night clubs and getting insightful knowledge about what it’s like to perform in front of people. But it was also around the same time many musicians were leaving the country because of the 1974 Revolution and the Red Terror atrocities that were soon to follow.

It just so happened that Alem was entering the music scene the same time there was a great shortage of bass guitarists. Alem says, “because of this sudden drop in musicians, I was frequently called on by nightclubs—even though I was still very early in my career. I began to play with the Zambezi club band, and it hadn’t even been a month or two before I began to play at bigger venues in the city.”

Alem recalls, “I heard that Menelik Wossenachew’s group needed a bassist. I wasn’t there too long before I heard that Venus club’s bassist also left the country. I then replaced an interim bassist they hired and there I was basically fully employed.”

Alem would do Fridays and Saturday evenings at Venus club and then immediately make his way to Taytu club to perform overnight.

“I’d work at Venus five days a week, there I worked with Ephrem Tamiru—I actually recorded “Zeraf” with Ephraim. At that point the bassist shortage got even worse—some leaving for America or Djibouti. Incidentally, the bassist that worked at Hilton, a famous and long-time instrumentalist in the music scene, found other work and went to Europe. I then had the opportunity to replace the bassist at Hilton and it was there that I really learned so much especially with Walias band. It was actually around the time where I played for Tilahun Gessesse’s “Shole Yanech Tela.” I was also the original bassist who recorded for Muluken Melesse’s “Nigerigne Minew,” Alem says.

Alemseged emphasizes that since there was little access to formal instruction, skills like these could only be developed by teaching oneself or one another. In this way, surrounding oneself by those in the music scene was instrumental to one’s future success. Dereje Mekonnen, who was a keyboardist for Ibex Band, was Alemseged’s best friend and someone who’d share the tips and tricks he learned as a performer.

Alemseged’s career then took him to El-Gadarif and Kassala, cities in Sudan, where a two-month contract with Blue Nile band ended up lasting two years. Alemseged made his way to Cairo with fellow band members Hualashet and Tewodros Mitiku. There they stayed almost two years, fully supporting themselves and learning a thing or two from Egyptian musicians. It was shortly after that Alemseged acquired a special visa to Canada.

Alemseged tells me, “We got acquainted with the clubs [in Canada] and I also began to take classes. That’s where I learned the approaches and structures of American Jazz. I made my own compositions, learned how to play piano, and managed to incorporate both the bass and piano into my compositions. I also had family and musician friends in the U.S., so I’d go back and forth.”

He continues, “It was at this point we formed Demera band. Through Mohammed Al Amoudi’s support, we were able to get funding. It was really difficult at the time for musicians to support themselves and travel while doing so considering all the hotel fees, transportation fees, and so on.”

It was with Demera that Alemseged returned to Addis, right around the time EPRDF took over. Despite the uneasiness surrounding the political tensions and even technical issues like the lack of wireless microphone, Demera preformed for a huge crowd in a stadium.

Alemseged remembers it fondly: “There were so many people in the stadium—even the Prime Minister was there. There were videos that were recorded of the performance but because of politics, it was blocked from airing on ETV. I don’t even know where those videos are now. There were those who privately recorded the performance, but there really wasn’t much documentation (that we could easily find now).”

It was with this hefty musical experience Alemseged supported and toured with Ethiopian legends like Tilahun Gessesse, Menelik Wossenachew on his Gash Jembere album, Aster Aweke on her album Ebo, Bezawork Asfaw on Tizita, and Alem Kebede on Arada.

However, as his career and experience grew, it seemed that Ethio-jazz was ironically receding among Ethiopians. Alem says, “There were a lot of non-Ethiopians playing Ethio-style jazz that were becoming inadvertent representatives of our music. So, in the wake of that, we felt the need to create a band that could challenge that.”

This is part of why Alemseged’s current group, Feedel band, was born—to bring not only others but a new generation of Ethiopian artists and music enthusiasts back into the rich sounds that is Ethio-jazz.

Alem more recently has also been touring the world with legend Hailu Mergia: “I began working with him back in 2011 and went to London, Manchester, Norwich, Leeds, and Margaret, with him. We also went to Dublin, Ireland, as well as Scotland. We went to Germany, Sweden, France, Switzerland, Finland, and Italy. We also went to Thailand—probably the farthest we’ve gone.”

More recently, Alemseged has also been working on solo projects and has more upcoming festival performances in Europe. These projects are also undertaken in response to his concern about the state of Ethiopian jazz today. Alemseged explains, “The main reason I started this project was because I was concerned with the trajectory of Ethiopian music. Where’s it going?”

He tells me he’s of the opinion that, “musicians, to the best of the abilities, me included, have the responsibility to develop and make known our country’s music. Even foreign audiences love it when we preform our own music. This is why people in France, U.S., and Britian house the works of Alemayehu Eshete, Tilahun Gessesse, and Mahmud Ahmed. There’s actually a musician from France who travels the world by singing translated Mahmud Ahmed songs. So, this raises the question of how we ourselves can showcase our rich musical history.”

Alemseged hails from a certain historical musical tradition that has made its mark like no other genre coming out of Ethiopia. With this comes sage advice new Ethiopian artists can benefit from; so, I asked him whether he thought young musicians today have the responsibility to keep Ethio-Jazz alive and if so, what would be his advice?

“If artists really dig deep into their own roots, create and preform music that comes from this home base—they will always find an audience. I’ve seen this by hearing bands from places like Morrocco or Senegal—bands that revive and play their country’s music,” he testifies.

Alemseged advises that “this new generation of Ethiopian artists, to the best of their abilities, need to incorporate, thorough their own interpretations and innovations, aspects of Ethiopian tunes that are already there. To represent ourselves on the world stage by using Tizita, Ambassel, Anchihoye, and Bati (the Ethiopian pentatonic scales).

“The Ethiopian artist now should be concerned with not only using these tunes but also developing, improving, and innovating them. This will prove beneficial for the longevity of Ethiopian music even if it may not seem worth it in the short-term.”

BY SOLYANA BEKELE

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD WEDNESDAY 18 SEPTEMBER 2024