Ethiopia and Egypt are historically intertwined. The two countries are connected by Nile bloodline. Conflicts and cooperation along the Nile river go back as far as the time of the pharos. The word Nile is probably derived from sematic root “nahal” meaning river valley, which later took the forms “Neilos” in Greek and “Nilus” in Latin. The Nile River is the longest in Africa and the world at large. The river is 6,825km long and has a drainage area of 3.1million extending from south of the Equator to the Mediterranean Sea. The Basin includes territories of about 11 countries; Burundi, Rwanda, Egypt, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Tanzania, Sudan, Congo, Uganda and South Sudan. The Nile Basin is shared by 280 million people across these countries. The basin is one of the largest in the world. Despite this, many countries in the region face a water deficit, economic development needs have placed additional strains on the water resources.

According to historians, the rulers of Egypt, long ago, used to send gifts to the rulers of Ethiopia to ensure an uninterrupted flow of the Nile river. The offering of such expensive gifts started long ago around the 11th century. This was partly based on the assumption that Ethiopians were capable of interrupting or diverting the flow of the Blue Nile. Richard Pankhurst described the situation that there was little evidence that the Ethiopians ever made plan for the diversion of the Nile, let alone that they would execute them. One may even doubt, whether changing the course of the Nile, however, much desired or feared overlay with the technological possibilities of the time.

Although Egypt and Ethiopia have no common borders, the two countries are linked by the Nile river and share common history and have been mutually interdependent. Ethiopia is the main source of the Nile water on which Egypt is dependent. Egypt has historically been the source of Patriarchs that remained key to the religious legitimacy for Ethiopian political establishment. (Pankhurst)

Development of Hydro-Politics

Egypt’s long-term stride to dominate the Nile water resources has been inherited from the colonial past. It has to come out from rhetoric of the past to capture the current realities. That is, it has to accept a move towards establishing agreements on equitable utilization of the Nile water.

If you see developments of hydro-politics in the region, following the fall of the Turkish rule in the Sudan in 1885, the Basin became a theatre for European intervention and domination that continued up to the middle of the last century.

After the Berlin conference of 1885, there was a formal division into zones of colonial influence. Most of the Basin- Egypt, Sudan and East African Nile Basin countries fell under the influence of Great Britain. At the turn of the century, Great Britain concluded three agreements that applied only to the upper riparian states.

They prohibited the undertaking of any construction without the British consent on the tributaries of the Nile. This included the 1891 agreement with Italy, the 1902 agreement with Ethiopia and the 1906 agreement with the Congo Free Sate. Furthermore, subsequent to the 1902 agreement, a second formal treaty connected with the Nile waters in the so-called Tripartite agreement between Great Britain, France, and Italy was signed in London on December 13, 1906, without consulting Ethiopia. This was strongly rejected by Emperor Menilik as a sinister design against the sovereign state of Ethiopia.

The Aswan Dam, completed in 1902, marked the beginning of expansion of modern irrigation in Egypt. The main goal of the British policy was to expand cotton production for textile industries in Britain. Following the reconquest of the Sudan in 1899, further plans were made for the expansion of irrigation, mainly for cotton production, both in the Sudan and Egypt. In order to secure for over-year, storage of equatorial lakes and Lake Tana for flood control in the Sudan and timely water security for Egypt needed the 1929 new water agreement which was concluded only between Egypt and Great Britain. In this agreement, Egypt recognized Sudan’s right to water adequate enough for its own development so long as Egypt’s “natural and historic rights” were protected. Ethiopia did not recognize the validity of this agreement, nor did it ever accept Egypt’s claim to acquired or historic rights.

Up until the time Egypt and Sudan re-resolved the Nile question in1959, the Sudan had established rights to only 4BCM, compared to Egypt’s 48BCM, while 32BCM of the flood water found its way to the sea. The two countries allocated 55.5 and 18.5 BCM respectively according to the 1959 agreement signed only by the two countries.

Egypt’s concern over the Sudan centered on the fact that her very existence depended on the water of the Nile, whose source was believed to be the Sudan. No Egyptian government could entertain a hostile foreign power controlling the Nile from Khartoum. For instance, the railway from Khartoum to Port Said gave the Sudan outlet in 1906, for the trade independent of Egypt, the opening gate was described by the Cairo press as “the day of Egypt’s funeral”.

The international community and the upper stream states are being told that Egypt is making use of all available water and will do the same with any potential water. Egyptian policy proposes a 25% increase in Egypt’s irrigated area. The pace at which utilization of the Nile resources are being significantly slowed during the past decades in the Sudan because of political and economic unrest. The intent of the Sudan to use the full “entitlement” and it watches carefully the ways which Egypt utilizes its water, especially the transfer of water to poor lands in the Sinai vs. the talks in Egypt for exporting Nile water across Sinai in 1979.

Sudan has remained a backyard of Egypt for numerous historical reasons. That is, associations established a “semi-colonial” relationship since British Colonialism since the late 19th century. Thus, Egypt’s upper-hand and political leverage to put all pressures on Sudan allowed Cairo to obtain much more than is warranted by the agreements.

Despite the fact that Ethiopia contributes the highest proportion of water; 86% to the Nile (which is almost the River’s water flow) the relationship of Egypt and Ethiopia has always been full of suspicion and uncertainties.

It is unrealistic to imagine a large configuration of Ethiopia and Egypt in the current political debacle. Even if we recall developments in contemporary history, Egypt has been attacking Ethiopia on several occasions.

For instance, the Egyptian expeditionary army under Khedive Ismael, invaded Ethiopia to occupy the Blue Nile Basin and was defeated by Emperor Yohannes IV, at the battles of Gundet and Gura in 1876 and 1877, respectively.

Egypt has been a safe haven for any anti-Ethiopian forces or dissidents during any regime of Ethiopia. ELF was formed in Cairo in 1962. The Somali irredentist movements were provided with all-round support from Cairo. The Cairo broadcasting network had Amharic program served as a tool to disseminate hostile propaganda campaign against Ethiopia. Egypt has always been taking opposite stance to Ethiopian positions on many regional and sub-regional issues.

These are some of many instances that Egypt has been pursuing hostile policies towards Ethiopian strive for development. Egypt threatened to use the military whenever it felt Ethiopia was engaged in water projects that might reduce the amount of water in the Blue Nile. For example, according to some observers there had been eight instances where threats of war and conflict-enticing statements were issued by Egyptian leaders and politicians between the end of 1970s and the year 2000.

Geo-Political Dynamics

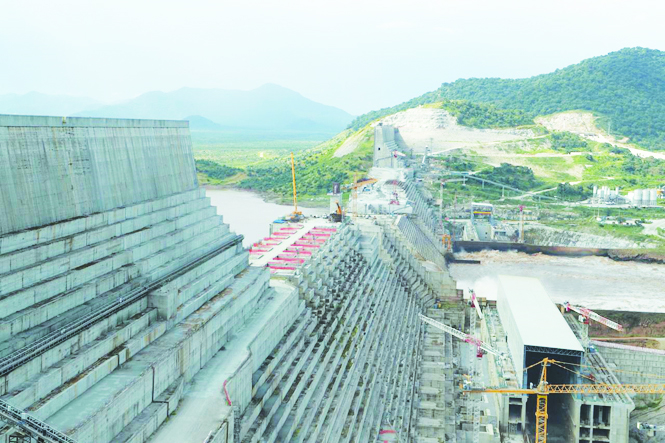

Ethiopia and Egypt have been at odds over the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), believed to be the largest hydro-electric dam in Africa. The dam is located on Ethiopia’s flank of the Blue Nile, just 12 miles from its border to the Sudan. It is believed that, “this USD 5 billion self-financed project, located on an ideal geographic location, will generate 6,000 MW or 15,860 GWH capital/year- that is twice the energy generated from the High Aswan Dam (HAD)”.

It is a fact that for Ethiopia to sustain its growth, it needs to meet an annual 32% growth in energy demand. Ethiopia doesn’t have other economically and technically feasible source of energy such as gas or oil for its energy requirements.

Ethiopia has an acute shortage of electricity with 65% of the population not connected to the grid. When completed, the Renaissance Dam is expected to benefit neighboring countries, including Sudan, South Sudan, Kenya, Djibouti and Eritrea from the Power generated. In fact, there’s an added advantage for the Sudan in that the flow of the river would be regulated by the Dam, which means that it would be the same all year-round in the country consistently which has been suffering from serious floods in August and September.

Endowed with enormous hydro-power potential, Ethiopia cannot afford to ignore its development endeavors. Egypt’s long-term strategy to intervene in a manner of stopping Ethiopia from taping into its hydro-power potential is tantamount to ill-will towards longsuffering people and evil desire to keep Ethiopians in abject poverty. Although Ethiopia is aptly described as the water tower of eastern Africa, it receives no water from another state, but gives away water to all neighbors. That is, Ethiopia gives away more water down its Nile tributaries than it retains, from the annual rainfall in its soil profiles. The Ethiopian highlands are the main source of water to Egypt, Sudan and Somalia through the Blue Nile, Atbara and Sobat Rivers of the Nile system and the Wabi-Shebele of the Juba Systems.

However, the development of upstream water has always been a source of grave anxiety to Egypt. Egypt has always turned a deaf ear to Ethiopia’s intentions to develop its Nile water tributaries. It regards the 1959 Nile waters agreement as defining its minimal entitlement. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in no way causes significant harm to the downstream countries.

In 2015, Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt agreed on a Declaration of Principle (DOP) that stipulated an equitable and reasonable “utilization of the Nile that will cause no significant harm” to other riparian countries. Numerous three-way talks between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia over operating the dam and filling its reservoir have been made for the implementation of the agreement.

According to the statements of Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy of Ethiopia, “Ethiopia, as the owner the GERD, will commence first filling of the GERD in parallel with the construction of the dam in accordance with the principles of equitable and reasonable utilization and the causing of no significant harm as provided under the agreement of Declaration of Principles (DoP) signed in Khartoum in 2015.

Breaking the Deadlock

Ethiopia and Egypt have been at logger-heads over the construction of the GERD. The deadlock has been increasingly bitter in recent months with Egypt saying it would use “any available means” to defend its interests.

Diplomatic engagement to resolve the situation and ensure peace and tranquility is decisive to the current and recurrent debacle between the two countries. Many efforts are being made in terms of exploring a comprehensive approach to solve the long-standing problems. However, all efforts will remain futile without a broader vision of accepting proposals to negotiate in good faith on the basis of the principles of equitable utilization of the Nile water resources.

Many hydro-politicians recognize that resolving international disputes over water is a complex problem in law and diplomacy and settling these international issues would certainly be a wise and useful achievement. This effort, indeed, requires the most expeditious and equitable resolution of conflicts.

In the 20th century, the process of rapid population growth and agricultural expansion has pushed into the reaches of the upper Nile river systems, so that actual or potential conflicts of interest emerge. As upper stream population has increased, agricultural development and industrialization, including the need for hydro-electric dams, became evident. This situation evoked legal principles to nullify downstream claims to acquired rights. Ethiopia’s consistent claim, to equitable utilization of the Nile River causing no significant harm to downstream states, has been critical for its development endeavors.

There are comments regarding the possibilities of armed conflicts in the Nile basin. Some of the comments include no matter how acute the crisis may emerge in the coming years over water supply in the drainage basin, armed conflict is not likely to be an outcome. New supply-demand equilibria will not be achieved through warfare and seizure of water resources, rather ends-up in disruptive adjustments within riparian states.

For the most part, water dispute in the Nile basin have remained below the military level with some exceptions. The first was, Fashoda incident of 1898, which was resolved without bloodshed. However, there have been a number of tense moments. In 1925, after the assassination of Lee Stack by Egyptian Nationalists, Britain punished Egypt itself by allowing the Sudan to begin a design of the Sennar Dam on the Blue Nile and the irrigation grid that was to become the Gezera scheme.

Therefore, what is urgently needed is building mutual confidence and commitment to negotiate in good faith based on the principle of equitable utilization of the Nile water resources as underlined by the principles of international law. It should be emphasized that Ethiopia cannot be expected to postpone indefinitely the utilization of its water resources for its development plans.

Contributor – Beide Melaku is a retired Ethiopian Diplomat who formerly served as senior diplomat at different Ethiopian missions abroad, namely Ghana, Kenya, South Africa and Italy.

The Ethiopian Herald June 25/2020

BY BEIDE MELAKU