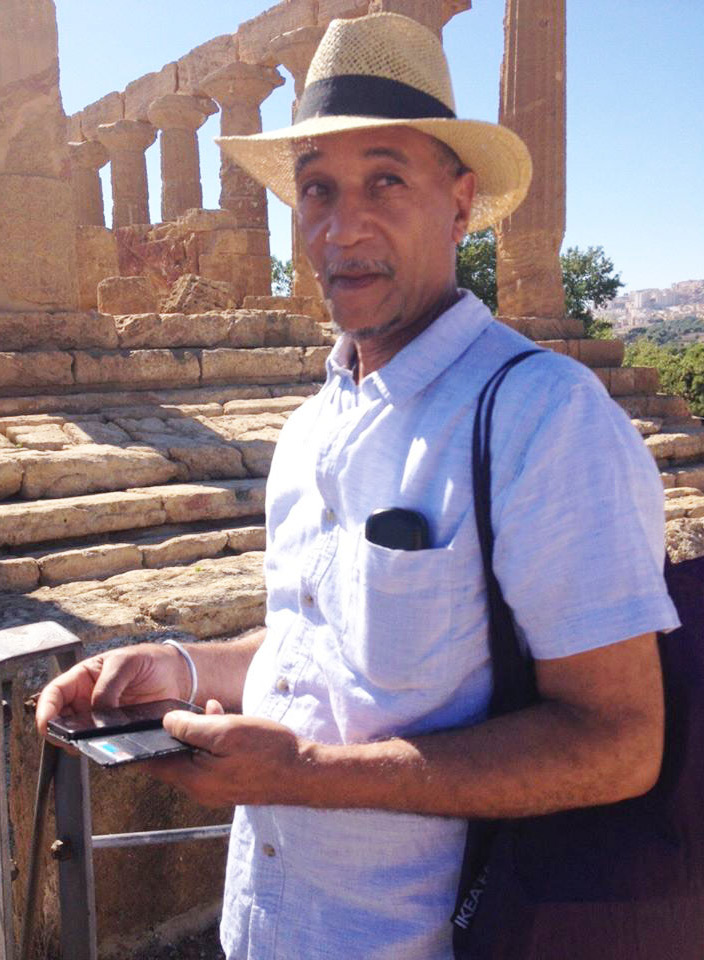

The Ethiopian Herald has stood the chance of intercepting the versatile black freedom exponent Amon Saba Saakana, Ph.D. This interview is A to Z a must read as it touches a wide spectrum of issues like African literature, science, politics, religion, education, homegrown knowledge, subtle ways of subjugations, ways of warding off such subjugations, black freedom movement, clearing confusions, different film sponsorship questions and identity crisis of this generation in the 3rd and second world.

He is a famous poet, author, playwright, novelist and researcher. Excerpts:

The Ethiopian Herald: To begin with could you brief us about your bio-data including your educational background and other related information? Do tell us also how you were attracted towards literature as well as the ups and downs you faced in your literary engagement.

Amon Saba Saakana, Ph.D: I was born in Trinidad, Tobago and left for London, UK, with my siblings in 1965. I started freelance journalism in 1969, writing for what we call the “underground” press, i.e., non-mainstream. I studied playwriting at Mountview Threatre School for one year. The school was geared towards reproducing British and European conceptions of theatre and language and did not accommodate other approaches.

I broke into a non-mainstream weekly magazine, Time Out, for which I wrote a book, record and drama reviews and cover features. I also did a lot of record reviews and interviews for the musical press: Melody Maker, New Musical Express, Sounds, Black Echoes, all now extinct with the coming of the internet. I wrote the scenario and conducted a number of interviews in 1970 for the BBC TV aired programme, Reggae, directed by Horace Ové, a fellow Trinidadian filmmaker. This later led to my first nonfiction book, Jah Music: The Development of Jamaica Popular Music, Heinemann, 1980, the first history of Jamaican popular music.

Luckily, I belonged to a Black Arts group and met Ed Bullins, an African American playwright, who had several of his plays produced in the UK. He gave me an open invitation to come to the US and I stayed with his family in 1970 (he brought his girlfriend he had met in London to New York and later married her). To keep me in pocket I taught his children reading and writing English. Bullins became an extremely successful playwright, at one stage having two reviewers examine his work on the front page of the arts section of the New York Times. Bullins also got me a job at Marymount College, a girls’ school, as a drama tutor, and also got me a job as assistant editor at the New York Festival Public Theatre which went into publishing two drama journals, one for play scripts, the other for reviews, features, interviews and performance.

I have always admired the dense and polemical poetry of LeRoi Jones (who later changed his name to Amiri Baraka) since I was seventeen years old, and had the opportunity of seeing his theatre and poetry work with the NewArk Players of which he was director. Jones had won the prestigious Obie award for his 1964 play, Dutchman, which was later made into an arts film by a British film director.

On my return from Britain in 1974 I made drama reviews contributions to Britain’s then main monthly drama magazine, Plays & Players. I had one of my plays, Soul of the Nation, produced at the Royal Court Theatre in 1975, and then moved to the Roundhouse for a two week run. The play was a take on Black Power and the levels of insincerity and dishonesty in some of its leading characters. It also showed the hand of the law in the British courts.

Having appeared in numerous newspapers and anthologies while in New York, and benefitting from Jones/Baraka’s community arts work, I sought out a four story building, rent free, from the Notting Hill Housing Trust, and turned it into an arts Centre. We started out as a purely Caribbean organization, but later embraced the entire spectrum of the world African community. We put on photographic, painting, ceramics exhibitions and conducted classes in African languages like Igbo and Yoruba. We also organized weekly lectures on a wide range of topics. One of the persons I worked with was Alem Mezgebe, a now deceased Ethiopian (born in Eritrea) playwright, who had a successful play, Pulse, on at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, which I later published.

Some of the artists I worked with, as director of Karnak House, are Emmanuel Jegede, sculptor, painter (born Nigeria), Charles Sambono, artist (born Zambia), Babatunde Banjoko, commercial artist and painter (Nigerian-born, Paris-based), Seheri Sujai (Grenada-born, London based), my wife and art director of Karnak House Publishers, Horace Ové (Trinidadian born, British based), filmmaker and photographer, Erroll Lloyd, artist (Jamaican), Lance Watson, photographer (Jamaican), Norman Reid, photographer (Jamaican), Vernon St. Hilaire, photographer (St. Lucian).

We decided in 1979 to start up a publishing company called Karnak House. The second book we published was a collection of poetry entitled I is a long memoried woman, in 1983 which won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize and we were the first African (“black”) owned press to win the award. It was later made into a Channel 4 TV production, is in the National Sound Archives in the UK, and has appeared in numerous anthologies and languages around the world. In 1985 my debut novel, Blues Dance, was published to a warm reception and I was given a full-page interview by feature writer Polly Toynbee in the Guardian. The book sold out in nine months and I have just revised it for republication in 2020.

While working at Karnak House, a number of African and Caribbean graduates searched me out for information and consultation on their thesis. This inspired me to formally attend university as a matured student (32). I was under the fierce supervision of now deceased South African Professor, Ken Parker. For my diploma I produced the book, The Colonial Legacy in Caribbean Literature. The book examined the social and political histories of the colonial Caribbean and the school system which emphasized a European syllabus, whether from Britain or France, and the impact this had on the writing of Caribbean writers. The preface was written by Ngugi Wa Thiong’o.

I had nine months left to complete the BA but Ken advised me that I was wasting my time doing that, he would put me on the MA course. For the MA I produced the thesis, later published as a book in 1997, Colonialism & the Destruction of the Mind: Psychosocial issues of race, sexuality, class and gender in the novels of Roy Heath.

I was later amazed that Blackwells, a well-heeled Oxford bookseller, kept reordering the book until it sold 100 copies to one bookshop! For this study I had delved deeply into the psychoanalytical approach which British psychologists may have been interested in, which may account for the Blackwells sales.

I started a Ph.D. at the School of Oriental and African Studies under a European South

African. She kept telling me how great my work was and offered no criticism. I distrusted that and, after two years there, I moved to Goldsmiths College. At the interview the Head of Department, when she learned my thesis would be on the representation of the African on the London stage, tried to dissuade me by telling me “sod the Afro- Caribbean.” Luckily, I never listened to her and I found a new supervisor, a Jewish South African. I completed the doctoral thesis in 1995, Sites of Conflict, Identity, and Sexuality & Reproduction: European Mythological Imaging of the African on the London Stage 1908–1939, which is not yet published.

My latest book is Djehuty/Hermes, Foundational Philosopher, in the Italian Renaissance. There are a number of books that deal with this Kmtan (Ancient Egyptian) figure, and I think my emphasis is his African origin and the deep antiquity of his emergence in history. His works were discovered by the Greeks when they had conquered Kmt in 332 BCE and they canonised and extolled him. It was during the murderous campaign of the Inquisition in which hundreds of thousands of female herbalists and earth scientists were burnt at the stake or imprisoned and various priests-philosophers, such as Ficino, Miradolla and the greatest Giovanni Bruno were vigorously questioning the limits of the Bible and the lecherous, murderous and blasphemous behavior of the church fathers. This led them to rediscover Djehuty/Hermes who appeared as the leading protagonist in the book, The Corpus Hermeticum. De Medici, who financially supported Ficino and employed him as a translator, and was also the patron of the Plato Academy, ordered Ficino to stop translating Plato and start immediately on Djehuty/Hermes. This was the book that was the primary philosophical influence on the birth of the Italian Renaissance. All scholars agreed on this, but from the early Greeks’ discovery, he had lost his Kmtan identity and was portrayed by both Greeks and Romans as a European! My thesis in the book is that Djehuty represented sacred initiation to higher knowledge which can only be obtained through initiation. All traditional African societies have these educational structures, and today exact and similar philosophies can be found not only in Africa, but in the dispersed African world, e.g., the Caribbean.

Herald: What is your take on African Literature?

Amon Saba Saakana Ph.D: I taught a course for two years at the College of Science, Technology & Applied Arts Trinidad and Tobago. I used the comparative literature method and did not follow the syllabus which recommended Shakespeare and Derek Walcott. I chose three books: The Voice by Gabriel Okara, Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid, and No Pain like this Body by Harold Sonny Ladoo. Okara is from Nigeria, Kincaid from Antigua and Ladoo from Trinidad, two African and one Indo-Trinidadian. The unity of the novels was the theme of colonialism and its effect upon social and cultural behavior. I used political and social history combined with psychoanalysis and linguistics to examine the novels.

This course caused uproar among some students as it did not follow the syllabus, and one student, in the first week, told her friend that I was mad. At the end of the course, when I brought up the subject, she confessed she was the guilty one but stated she had never been exposed to such approaches before and she felt that she understood herself and her society better as a result. Another student, a matured prison officer, said he speaks creole (non-standard English) but reading it was difficult. He said that shows the extent to which our culture was not authenticated in the education system.

This holds for contemporary African literature. Colonization has been with us since the Persians, later Greeks and Romans who conquered the African civilization of Northeast Africa, Kmt (Ancient Egypt) from the 6th century BCE. This led to the destruction of a major civilization, which succeeding European nations completed up to today by holding the economic reigns of power of the whole of Africa. Islamic North Africa had a head start from its colonization of Egypt in the 7th century, and its large scale captivity, enslavement and castration of African men and the harnessing of the African woman as domestic laborer and child-breeder, followed by unremitting proselytization of the religion in the far corners of Africa. Christianity too was a tool of European penetration and though Ethiopia’s Christianity is well established before European penetration, it tied itself historically and religiously to Israel.

We thus have a complexity of psychological indoctrination, cultural assimilation and economic stranglehold, maintained by murder and bloodshed as in the Congo, and the tyranny of France and Britain in deposing, imprisoning and exacting cruelty on rebelling populations, and the delusion of independence is reflected in the funding of the AU by Europe. We are faced with internal dissention and the colonial introduction of ethnic affiliations where historically African kingdoms shared cultural and educational knowledge’s across borders.

We have made big strides over the last twenty years particularly with the literary perspective of women writers from all over the continent. I pinpoint the spearheading of this movement with the publication of the Egyptian writer and activist Nawal El Saadawi’s monumental novel, God Dies by the Nile, a cruel and exploitative male world unimagined in one’s wildest dreams. The female world has been opened up and she has searchingly documented the lives of families as they stride through modern (post)colonial polities.

African literature has proven to have the longest lasting literary history on the planet as we can trace literary tales back to Kmt (Ancient Egypt) from the third millennium BCE to the present time. Comparatively, Mesopotamia had no literary tales until the middle of the third millennium and their alphabet produced no descendants unlike Kmt from which we can trace Greek, to Latin, to modern English. Unfortunately for most of us, we are ignorant of our history and comparative African and world history is not taught on the African continent.

It will take a renaissance, for which Africa is well known from the time of the Pharaohs’ weheme mesu, repetition of the birth, i.e., Sankofa (Ghanaian gold weight figure), a bird with its head turned to its back: go back and fetch it, of which visible signs are already manifesting, to revive African cultural standards. The Western world has benefitted enormously from African literary history, the philosophy of Aesop, who gave advice to Greek and Persian kings, and whose work is still in existence today after nearly 2,500 years. All the monuments, civilizations, writings are still with us today, but these have not been made fundamental instruments of our liberation because African governments in the main look to Euro-America for paradigms of development when the only paradigm they have established is plunder, looting, murder and resource extraction and massive exploitation. Not a single religious movement has emerged from Europe or the United States. And many of the inventions that propelled the late 19th and 20th/21st centuries have been created by Africans living in the oppressors’ world.

Herald: How should Africans blend their traditional knowledge with modern way of life? How could they promote that in literature?

Amon: Without apology I believe African individuals are the most continuously inventive people in the world but horribly kept back by backward governance in which innovation is not supported, and the latest inventions (masterminded, in numerous instances, by African genius outside the continent) and fads from abroad are readily adopted. In the area of filmmaking we have seen a plethora of innovative films that blend tradition and modernity. This experiment is not confined to one geographical area of Africa but from Mali, Senegal, Ghana and Ethiopia as random examples. First of all, films influence mass populations more rapidly than books, and the high standards obtained in these countries are astonishing. Yet they are not sufficiently subsidized either by central or regional government or by businesses, and the artist is forced to struggle to raise funds to produce his/her films. The successful Ethiopian filmmaker, Haile Gerima, took eight years to raise the finance for his independent film, Sankofa, which was his most financially successful film to date. I suggest the audience is out there to support the filmmaker’s work but the latter has to go begging in Europe in order to realize finances.

In the plastic arts individual African artists’ work are fetching substantial sums. Recently, the deceased Nigerian artist, Ben Enwonwu, had one painting auctioned at Christie’s that sold for 1.4 million US dollars. Chris Ofili’s work has been sold for over 2.5 million US dollars. Ghanaian and Malian artists are also fetching astonishing sums and producing work within the African tradition inclusive of references to modernity.

The problem with financial reward is that art patrons of the West are the ones who invest in art, a nation’s patrimony, which is held in overseas institutions or in the largest art warehouse in the world, in Brussels, Belgium. The ideal situation for all the arts is a desired responsiveness from continental audiences who can benefit psychologically and culturally from the arts of African artists. In time, the continent will determine the human/moral value of an artist’s work and thus his/her financial worth. The time is not too far off when African artists will no longer create to accommodate trends in Western art in which they imagine the attraction of foreigners. If that were so, why is the thousands of traditional African artifacts looted and housed in the highest art institutions in Britain, France, Belgium, USA etc.?

Herald: How did you see the contribution of African literature to world literature, modernity & science?

Amon: One fact we must never lose sight of is that Western colonialism and media propaganda have humiliated and degraded the African to a status of an inferior being and using the standards of Western models, we have bleached our skins, permed and straightened our hair, donned Western clothes and fell in trance with Western food, in short, disfigured ourselves in pursuit of empowering ourselves through identification with the magnificent white lie. Of course, disfigurement is the objective of Western propaganda and they have successfully done so.

But, the caveat for me is the persistence of African traditional forms in the approach to learning. It is now clear without a doubt that young Africans have the scientific imagination to propel a significant change in the development of African technology and science. Thus the invention of an electric car, by a formally unschooled Zimbabwean, that does not require recharging has gone beyond Tesla, and everything that is currently on the market. His invention involves harnessing electromagnetism, resident in our atmosphere, to keep the vehicle continuously charged. I suggest all these scientific principles are enshrined in African secret societies and have not been exposed to the general public. The scientific principle is fundamental to African secret societies which were really depositories and propagators of advanced knowledge of our universe but never harnessed for a number of reasons. Several traditional practitioners have bequeathed a wealth of knowledge which is not dependent upon Western knowledge systems. After all, in the United States, for example, an African enslaved provided the secrets of curing malaria but was never credited for it. A Congolese medical doctor has found the antidote for Ebola, a legally patented disease which deliberately created such havoc in Central and West African countries. It was a Ghanaian who was tasked with inventing fiber optics and a Nigerian who made possible infinitely multistage of the internet. And it was a South African butcher who performed the first heart transplant in the world, though claimed by Dr. Bernard (who discovered and recruited him for the job); though in later life he was credited with the operation. These are random samples of the meaningful African contributions to our modern life that go unheralded, whether in spacecraft design, atomic energy, eye surgery,etc.

The point is individual Africans are far ahead of backward African governments that do not see beyond the next corrupt act of recipients of bribes and the impoverished selling off of African resources.

In our current technological world, if big African businesses do not harness the immensely inventive scientific community that we have, we may not make it through the 21st century, because not only are African governments not doing it but the bureaucracy involved, for example, in implementing a continental-wide free trade zone, is otherwise empowering Chinese penetration and the continuance of European control because of African inferiority complexes and the personal bribes they accept.

The primary task is the abandonment of inherited colonial structures which were meant to impoverish Africans, belittle and humiliate them, while attractively enriching themselves.

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD SUNDAY EDITION 8 DECEMBER 2019

BY AMBO MEKASSA