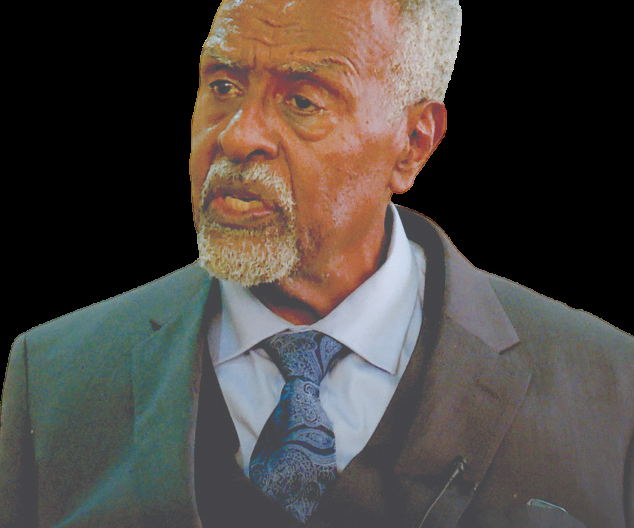

Professor Gebisa Ejeta, an Ethiopian-American plant breeder and geneticist, distinguished Professor at Purdue University, and winner of the prestigious World Food Prize for his major contributions to sorghum production, has now received the most coveted U.S. National Medal of Science from the President of the United States at the White House. The award is the nation’s highest recognition for scientists. According to the White House, Professor Gebisa was honored for outstanding contributions to the science of plant genetics.

His work has focused on developing drought-tolerant and Striga-resistant sorghum varieties, which have been instrumental in enhancing food security in many African nations. Striga, commonly known as witch weed, is a parasitic weed that severely affects the yield of crops like sorghum.

Professor Gebisa Ejeta is a towering figure in the world of agricultural science and food security, a globally acclaimed laureate and advisor. His life and work stand as a shining beacon of the world and an example of what dedication, excellence, and love for one’s country and profession can achieve on the world stage.

For his academic excellence and achievement, in 2011, President Barack Obama appointed Gebisa Ejeta as a Member of Board for International Food and Agricultural Development. In 2023, the National Medal of Science was awarded to Ejeta by President Biden.

The respected World Food Laureate Professor Gebisa Ejeta discussed with The Ethiopian Herald his educational journey, and the changes that must be made in the agricultural sector to guarantee food security and self-sufficiency in Ethiopia and Africa. Enjoy reading.

Would you tell us about your academic journey and achievements?

I believe almost everyone in Ethiopia has heard about my story. Just to recap, I am a child from west-central Ethiopia and grew up in a poor family. Thanks to the opportunities I received—largely due to my mother’s encouragement—I was able to get an education.

I attended school up to seventh grade in Olonkomi, the town where I was born. My mother was actively involved, urging me to study hard and achieve good scores. I then moved to eighth grade in Addis Alem, a city about 20 kilometers from Olonkomi. I managed to gain admission to one of the best schools in the country by attaining outstanding grades. As many have heard, I used to walk the 20 kilometers from Olonkomi to Addis Alem—or to Ejersa town—to attend school.

At the time, there were two agricultural high schools: Jimma Agricultural School and Ambo Agricultural High School. I completed my secondary education at the Jimma Agricultural Technical School. I chose Jimma, which was run by Americans from Oklahoma State University through the Point Four Program—an initiative aimed at supporting developing nations with technical expertise.

Attending Jimma for four years was the best opportunity I received. That school was my ticket out of poverty. Without it, I don’t know what I would have done—the next closest high school to my hometown was about 100 kilometers away, and I couldn’t walk that distance.

Jimma provided not just an education but also a nurturing environment. From there, I moved on to college and eventually graduate school. That high school opportunity, which I received at age 14, was foundational. I always credit that American-supported boarding school for giving me a new beginning and lifting me out of poverty.

How did you get the opportunity to join Haramaya University?

Back then, if you attended either Jimma or Ambo High School, you weren’t required to take the national Ethiopian School Leaving Certificate Examination (ESLCE). Instead, Alamaya College (now Haramaya University) would send its own entrance exam directly to the schools. If you scored well and had an average of three or above on your high school scores, you are qualified for admission.

I succeeded in that entrance exam and was admitted to Alamaya. Coming from an American-style high school in Jimma, the transition felt smooth. Our path was essentially moving from one American educational program to another. The learning environment at Alamaya was incredibly rewarding. The curriculum offered a balance between theoretical and practical knowledge.

In summary, I completed my secondary education at Jimma Agricultural Technical School, established in collaboration with Oklahoma State University, and graduated with honors. I then joined Haramaya University in 1973.

How did you spend your time at Haramaya?

We had access to a range of opportunities. I had already started playing basketball in high school, as I was growing tall at the time. When I joined Alamaya, I continued playing basketball for all four years. We had a successful sports program, and I also played volleyball.

Alongside sports, we had a solid academic foundation in science and technology. So, from both an educational and extracurricular standpoint, Haramaya offered a well-rounded experience. It was an invaluable opportunity for a young person like me.

What are the major challenges surrounding agricultural productivity in Ethiopia?

That’s a broad but important question. The short answer is: science and technology. While we’ve developed and acquired many agricultural technologies—both domestically and from abroad—the challenge has always been in delivery. We’ve struggled to consistently bring these technologies to farming communities in a sustainable, scalable manner.

Historically, most initiatives have operated in a project-based mode. But the roots of agricultural research in Ethiopia trace back to Jimma and Alamaya, with support from USAID. These early efforts led to the creation of the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) in the 1960s. Graduates from Jimma and Ambo played central roles in this foundational work.

So, while we’ve made strides in research and technological development, we now need to bridge the gap between research and practical implementation. The recent “Kuta Getem” (Cluster Farming) initiative is a positive step toward scaling up agricultural innovations.

To further boost productivity, we must build a robust private sector that can partner with government programs. This would allow for profitable, sustainable technology transfer to farmers. We also need to ensure that farmers have market access for their surplus, turning increased productivity into economic opportunity. It’s about more than just delivering technology—it’s about creating a full value chain from research to market.

How do you see the progress of Ethiopians in agricultural research?

I think it’s finally beginning to take off again. For a while, African agricultural research, in general, lagged. However, I must commend successive Ethiopian governments—from the monarchy, through the Derg, to the present—for consistently supporting research. We’ve outpaced many African countries in that regard.

That said, I believe agricultural research was stronger in the past. Some areas still show great promise, especially as universities become more involved. We need to shift some responsibilities from government to the private sector and give talented individuals the space and resources to thrive. With the right support, Ethiopia can once again become a leader in agricultural research.

What is your impression of Ethiopia’s efforts to ensure food security through the summer wheat program?

I’m impressed by the wheat flagship program. It has enabled a large number of farmers to access seeds, fertilizers, and mechanization. The push to grow wheat in the summer, using irrigation during the dry season, is a strategic move.

Ethiopia is already Africa’s largest wheat producer. In fact, we produce more wheat than all other African countries combined. Off-season irrigation farming has the potential to increase yields significantly and reduce dependency on rainfed agriculture.

In my view, we could meet all of our national wheat needs—and even produce a surplus—just through off-season farming. This would free up the main growing season for farmers to cultivate other essential crops, without being forced into a one-size-fits-all approach.

How can we fight the negative effects of climate change and ensure food security during recurrent droughts in Eastern Africa?

Climate change is real, but projections suggest that East Africa may actually experience more rainfall in the long term. Regardless, focusing on dry-season irrigation farming is a practical solution. Ethiopia is fortunate to have abundant rivers and diverse agroecological zones, giving us the flexibility to choose both what and when to grow.

What’s needed is a shift from project-based approaches to long-term commitments supported by the government. If we focus on major crops—like wheat, sorghum, corn, and legumes—and align them with their optimal growing environments, we can manage food production effectively.

Success also depends on discipline and commitment. In the past, older generations showed stronger follow-through. Today, we need to retain and support our brightest minds—both at home and abroad—and give them the tools to innovate, including digital technologies and advanced sensors to support precision agriculture.

If we train the youth properly, support innovation, and open pathways for private enterprise, we can reduce the burden on government and unlock new economic opportunities. I am confident that Ethiopia can surpass many other African countries in agricultural advancement.

How do you see Ethiopia’s current commitment to alleviating food insecurity and increasing productivity?

I’m very optimistic. If we restore the strong work ethic we had before and maintain government support for research, I believe there are no limits to what Ethiopian agriculture can achieve.

We have talented people, both inside and outside the country. If we can unite these talents and focus them on national goals, Ethiopia will no longer face food insecurity. We’ve already made major progress over the past decade. Despite numerous security challenges, widespread hunger has been largely avoided, which is no small achievement.

But to truly elevate our agricultural sector, we need peace. With peace, our human and natural resources can be fully mobilized. I believe the days of food insecurity in Africa can be behind us—if we also resolve broader issues of security and governance.

Ethiopia is a country with a rich agricultural history, abundant potential, and a resilient people. Elevating our agricultural science and technology is entirely within reach.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with The Ethiopian Herald.

It is my pleasure.

BY EPHREM ANDARGACHEW

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD SATURDAY 28 JUNE 2025