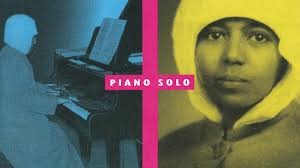

The piano as a music type or genre has a relatively long history in Ethiopia. If we take the first Ethiopian female pianist, Emahoy Tsegue-Mariam Gebrou, as a point of reference, we realize that she has been composing and playing piano pieces starting from the early years of the 20th century. Emahoy Tsege-Mariam was 100 years old as she was born in 1923 and died in March 2023. Modern critics have described her music as “melodic blues piano with rhythmically complex phrasing.” Piano was certainly known in Ethiopia before that period although the relevant information is not readily available.

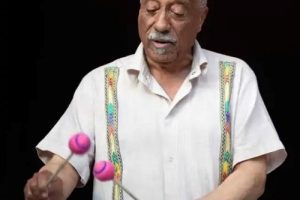

Girma Yifrashewa on the other hand is a more recent phenomenon as he was born in October 1967 in Addis and was educated at the Bulgarian State Conservatory of Music and started his career by playing the traditional krar, which is a stringed instrument played mostly solo or in a band. Although Girma is little known here in his native country, he is now an internationally acclaimed pianist whose skills are displayed at prestigious Western or American classical music venues like Carnegie Hall where he has presented his productions. He and Mulatu Astateke are the most internationally admired modern musicians in Ethiopia.

A lot is written about Girma in the foreign press. According to Music Africa, a website specializing in African music, “Girma Yifrashewa has now become a worthy new torchbearer of African pianism. His highly personalized approach to the piano likens him to Ethiopian composer Emahoy Tsege Mariam while his use of Ethiopian pentatonic scale within Western art Music format places his compositions in conversation with more academically minded work.” Girma’s albums include works like “the Shepherd with the Flute”, “Elilta”, “Meleya Keleme” and “Chewata”. He is no doubt one of the most illustrious composers alongside the likes Ashenafi Kebede in Ethiopian classical music.

It is important to note here the link between Emahoy Tsege Mariam’s style and Girma’s inspiration from it. As indicated in the quotation above, there is an organic link between the two remarkable musicians whose lives and works did not converge in time and space but retain the taste of one common origin, which is Ethiopian by identity and African by extension. Girma plays Ethiopian piano compositions to Western audiences, and this has not prevented him from displaying his talent or earning worldwide appreciation simply because music is a universal language. Music has such magic within it that we enjoy melodies without even knowing which country they come from, what their source is, or what genre of music they are.

For this reason, music, including piano, is often described as “an art concerned with combining vocal or instrumental sounds for beauty of form or emotional expression, usually according to cultural standards of rhythm, melody, and, in most Western music, harmony. Both the simple folk song and the complex electronic composition belong to the same activity, music. Both are humanly engineered; both are conceptual and auditory, and these factors have been present in music of all styles and all periods of history, throughout the world.”

Ethiopian piano compositions have all the hallmarks of their origin while they continue to move the hearts and souls of music lovers from one end of the world to the other. That is also the magic that has made those composers artistically immortal at the same time turning them into sources of inspiration for musicians from another generation.

Last week, a friend of mine on a visit to the United States gave me a buzz to tell me that he was going to visit Grma Yifrashewa, perhaps the best-known contemporary Ethiopian pianist who was in town preparing for a concert. It was a long time since I heard about Girma, the lone pianist much like Mulatu Astatke, the inventor if not pioneer of Ethio-Jazz music, the first of its kind in Africa. I asked my friend whether Girma was living in the US. He told me that he is based at home in Addis at, the Yared music where he is acting as its director not on a full-time basis but just as a freelancer, to use a term from journalism.

I referred to his official biography to check whether this was true and what I discovered was a surprise to me. Girma is referred to as a ‘self-employed’ person. He has no permanent employment, and he is often flying between his home in Addis to various destinations in Europe and America. So, Girma is currently in the US for a concert and that is terrific indeed. Ethiopians are no doubt finding a rare opportunity to listen to their acclaimed pianist, who has already made his country and Africa proud.

Piano both as an instrument and a style is not an Ethiopian or African music genre or instrument. It was rather imported from the West and blended with local melodies and the result is fantastic, like so many musical instruments that were first discovered and played in Europe. Even in the Western context, piano is an elite music, that was the exclusive domain or privilege of the aristocratic classes in the last few centuries.

In Ethiopia on the contrary, piano is less known by the public and less practiced by professionals for many reasons. First, it is not an easy-to-play musical instrument as it consists of a bulky table-like body and several keys that are put together to create sounds as soon as you touch the keys with your fingers. A more sophisticated definition of the piano is, “a keyboard instrument that produces sounds by striking strings with hammer, characterized by its large range and ability to play chord freely.”

The second reason for the piano’s relative obscurity and failure to capture the popular imagination in Ethiopia may be its price. According to available information, “the first pianos were too expensive for even the wealthy to own them. Even now, a piano is considered a very cumbersome and expensive instrument that cannot be available to a large number of people anywhere in the world. In Ethiopia, the average price of a modern Yamaha keyboard piano is estimated to be 26, 500 birr. This is not the big piano but a hand-held one which is small in size and limited in its functions.

“Piano was invented in Padua, Italy, by renowned harpsichord maker Bartolomeo Cristofori in the 1700s, the piano was initially called the gravicembalo col piano e forte, or “harpsichord that plays soft and loud” and looked almost like a piano. The full name of piano is “pianoforte”.

To this very day, Piano both as a musical instrument and a genre of music, (i.e. jazz-piano for instance) is not well known or popular in Ethiopia. Unlike Guitar, saxophone or drums, piano is considered a bit of an ‘elite musical instrument’ that was confined within small circles of music connoisseurs and practitioners.

As we said above, piano was introduced to Ethiopia rather early in the last century, but we still have a few players relative to other musicians who play different instruments. In almost a century, this country has produced only two or three prominent pianists deserving international acclaim. The new generation of young musicians might be intimidated by the absence of more pianists who could give them greater inspiration to join the music school and major in piano.

One alternative is to promote the piano both as a musical instrument and as a music genre. The fact that the piano cannot be easily affordable may be one hurdle although alternatives could be explored to produce the instrument here in Ethiopia. Piano is made from bamboo that can be planted here and provides the raw material for its production. The other alternative is to import cheaper brands of pianos that might be available in Chinese markets for instance. The love for music should also be developed among young people who display talent and musical inclinations in their earlier years.

It is to be recalled that the old and now-defunct imperial-era Ethiopian school curriculum included music as an independent subject to be given at many schools across the nation. However, during periods allocated for music study, youngsters would gather in their classes and sing songs and sometimes dance to their own melodies. It was rather a period of recreation that quickly degenerated into chaos and cacophony. That was not of course a productive or creative way of teaching music.

Nowadays there are better opportunities to study music. However, young people may be reluctant to join Yared Music School, the only official music school in the country, simply because there are no job opportunities after they graduate. You may remember the one-time popular group of young women who studied at Yared and were playing violin at hotels and restaurants because they could not get sponsors or employers. Musicians should not however face such a destiny of public and official neglect because this might hurt the development of arts and music in particular.

Music cannot be a universal language before becoming a national language that unites us, delights us, and moves us to enjoy the feeling of calm and ecstasy, in a world filled with chaos, sound, and fury.

BY MULUGETA GUDETA

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD THURSDAY 20 JUNE 2024