Poverty reduction Versus

population growth: UNDP’s latest verdict

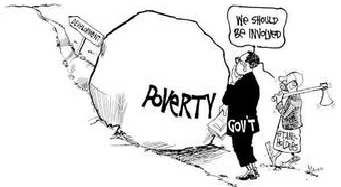

The rate at which population is growing in Ethiopia is faster than the rate at which poverty is being reduced, according to last week’s statistic highlighted in a media briefing by UNDP Resident Representative for Ethiopia Turhan Saleh and UNDP National Economist Haile Kibret in connection with the release of the 2019 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index is sobering (MPI). According to Turkish Anadolu News Agency, the report gives much food for thought although the demographic profile of Ethiopia has always been a subject of anxiety by the UN agency in previous years too.

The UNDP annual report sheds a balance light on Ethiopia’s achievements in poverty reduction over the last many years was stressing the deplorable conditions in which millions of children are still languishing in. It also sent a warning against the threat of uncontrolled population growth that is far outpacing poverty reduction efforts.

The worrisome conclusion aside, this is nevertheless a good opportunity for bringing the demographic challenge to the attention of African governments in general and the Ethiopian government in particular whose policy, if there is any population policy at all, was one of neglect if not leaving the issue to fate.

There is even a tendency to look at demographic growth as a sign of national strength without examining the underlining challenges economists are pointing at and policy makers are ignoring. Recent news about Ethiopia’s population going past the 100 million mark, did not sound any alarm among policy makers as well as stakeholders engaged in activities pertinent to stem this frightening demographic tide.

Population growth has always been a major theoretical challenges from Malthus to the present development economists. It has always been a practical challenge to policy makers particularly in the developing countries where effective mechanisms for coping with fast population growth has never been in place to this day.

From the theoretical point of view, classical economists like Malthus maintained that in the Europe of the time, agricultural production lagged behind population growth, these countries were said to be heading for trouble.

Malthus maintained that population tends to increase faster than the supply of food available for its needs. And if population growth too much faster than the food production, the growth is checked by famines, disease and war.

Malthus’s theory of population was widely accepted until the 20th century when population dynamics faced new challenges and a critical revisiting of previously accepted theories. Nowadays Malthusian theory has marginal relevance to the complex issues shaping demographic change and its consequences. Nowadays, there is an interdisciplinary approach to addressing demographic issues.

As one study recently pointed out, “Links between development, environment, and demographic changes have been studied in depth for years, while links between population dynamics and sustainable development have been studied much less often. Attempts to empirically address connections between demographic factors and sustainable development often spark fundamental controversies in science and public discourse.

The UNDP report focused on the condition of children under 10 for obvious reason. This is the age group most vulnerable to poverty. This is the age group by which the condition of the general population is also defined. And the measurement or the methodology used to gauge the depth of poverty in which children are caught at present is not one dimensional.

The data is not compiled only from the point of view food consumption. It includes other factors such as water, sanitation, education, asset and income, among others. It has taken many factors into consideration. Food deficit can only be one component of the overall picture.

What is interesting about UNDP’s latest report is that its affirmation that the situation in the area of child welfare had improved in the recent past while the trend is deteriorating only in the last couple of years.

“Overall, MPI improved in 2011- 2016 in Ethiopia largely due, according to Saleh, to the right investments made by the government – investments in water, sanitation, education and health.” the report said.

The recent deterioration might be due to the massive population displacements that took place across the country as most of the displaced people are women and children, the two most vulnerable groups. Even with increased government investment, the challenge could not b addressed effectively due to the complex nature of the problem.

In the past, Ethiopia’s poverty was linked to uncontrolled demographic growth relative to available resources When more than 8 million people in Ethiopia need emergency food aid as they do at present the phenomena has no name other than famine whether the food crisis is due to production shortages or human displacements.

Ethiopia has in fact been a chronically food deficit country, sometimes facing cataclysmic famines of Biblical proportions throughout its history. Whether the country’s population was 10 million or 100 million, Ethiopia has been a country where most people go to bed without a decent dinner.

So, the problem lies not in demographics but somewhere else. Professor Mesfin Woldmariam, in his seminal work entitled Vulnerability to Famine in Northern Ethiopia, published at the height of the 1984-85 famine argues that food shortages in the country were not always caused by climatic or demographic factors but resulted from poor governance, poor policy, lack of freedom and accountability.

It would therefore be wrong to attribute Ethiopia’s recurrent famine to Malthusian precepts. Population is a factor in the overall picture but it is not the sole or the determining factor. Government policy is rather the basic cause of famine in 20th century Ethiopia, according to academics like Professor Mesfin and others.

A rather holistic approach is required either to understand Ethiopia’s famine or seek a feasible alternative to its demographic time bomb. Population growth is one factor among others in Ethiopia’s continued plight.

According to a study, “Ethiopia’s population has grown from 33.5 million in 1983 to 84.32 million in 2012. The population was only about 9 million in the 19th century. The 2007 Population and Housing Census results show that the population of Ethiopia grew at an average annual rate of 2.6 % between 1994 and 2007, down from 2.8 % during the period 1983-1994. Currently, the population growth rate is among the top ten countries in the world.

The population is forecast to grow to over 210 million by 2060., which would be an increase from 2011 estimates by a factor of about 2.5.” According to these figures. the demographic explosion in Ethiopia is not a figment of the imagination but a real and immediate danger.

And now the UNDP report on Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), focuses on child poverty by establishing a link between population growth and poverty reduction, that can also be applied to the overall population by extension, although the study has left aside the general population to concentrate on the condition of children.

Its verdict is incontrovertible. “The rate at which population is growing is faster than the rate at which poverty is being reduced.” In other words, Ethiopia’s demographic growth has become a time bomb that may frustrate its quest for poverty reduction and even attaining a much improved standard of living for the general population.

The underlining message is also clear: control your population or else you are going to see further erosion of the socio-economic gains made in the past. Population control is almost taboo in Ethiopia although policy makers sometimes pay lip service to its merits. There is no clear policy on this and less so when it comes to practical approaches to stop the galloping pace of demographic growth that is going to destroy the little that has been achieved in the recent past.

In this regard Ethiopia can learn from the Chinese who managed to bring down the rate of population growth significantly and almost made it commensurate with economic growth and have achieved a resounding success. It may be time for the Ethiopian government too to a realistic and feasible population control strategy before it would be too late to do so.

This is not to say that the “one child one family” policy the Chinese adopted would be suitable for Ethiopia that has to find its more suitable strategy to reduce not only child impoverishment but also poverty in general. In this sense, the UNDP latest statistics can be taken as both a warning and a wake-up call.

The Ethiopian Herald July 21/2019

BY MULUGETA GUDETA