Research scientists are studying groundwater resources in three African countries in order to understand the renewability of the source and how people can use it sustainably towards a green revolution in Africa.

“We don’t want to repeat some of the mistakes during the green revolution that has taken place in Asia, where people opted to use groundwater, then groundwater was overused and we ended up with a problem of sustainability,” said Richard Taylor, the principal investigator and a professor of Hydrogeology from the University College London (UCL).

Through a project known as Groundwater Futures in Sub-Saharan Africa (GroFutures), a team of 40 scientists from Africa and abroad have teamed up to develop a scientific basis and participatory management processes by which groundwater resources can be used sustainably for poverty alleviation.

Though the study is still ongoing, scientists can now tell how and when different major aquifers recharge, how they respond to different climatic shocks and extremes, and they are already looking for appropriate ways of boosting groundwater recharge for more sustainability.

“Our focus is on Tanzania, Ethiopia and Niger,” said Taylor. “These are three strategic laboratories in tropical Africa where we are expecting rapid development of agriculture and the increased need to irrigate,” he added.

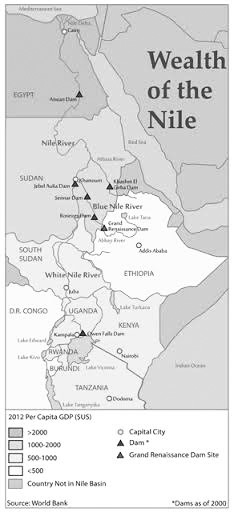

In Tanzania, scientists from UCL in collaboration with their colleagues from the local Sokoine University of Agriculture, the Ministry of Water and Irrigation and the WamiRuvu Basin Water Board, have been studying the Makutapora well field, which is the only source of water for the country’s capital city – Dodoma.

“This is demand-driven research because we have previously had conflicting data about the actual yield of this well field,” said Catherine Kongola, a government official who heads and manages a sub section of the WamiRuvu Basin in Central Tanzania. The WamiRuvu Basin comprises the country’s two major rivers of Wami and Ruvi and covers almost 70,000 square kilometres.

She notes that scientists are using modern techniques to study the behaviour of groundwater in relation to climate shocks and also human impact, as well as the quality of the water in different locations of the basin.

“Groundwater has always been regarded as a hidden resource. But using science, we can now understand how it behaves, and this will help with the formulation of appropriate policies for sustainability in the future,” she stated.

Already, the World Bank in collaboration with the Africa Development Bank intends to invest some nine billion dollars in irrigation on the African continent. This was announced during last year’s Africa Green Revolution Forum that was held in Kigali, Rwanda.

According to Rajiv Shah, the president of the Rockefeller Foundation, boosting irrigation is key to improving agricultural productivity in Africa.

“In each of the areas where we are working, people are already looking at groundwater as a key way of improving household income and livelihoods, but also improving food security, so that people are less dependent on imported food,” said Taylor. “But the big question is; where does the water come from?”

Since the 1960s, during the green revolution in Asia, India relied heavily on groundwater for irrigation, particularly on rice and wheat, in order to feed the growing population. But today, depletion of the groundwater in the country has become a national crisis, and it is primarily attributed to heavy abstraction for irrigation.

The depletion crisis remains a major challenge in many other places on the globe, including the United States and China where intensive agriculture is practiced.

“It is based on such experiences that we are working towards reducing uncertainty in the renewability and quantity of accessible groundwater to meet future demands for food, water and environmental services, while at the same time promoting inclusion of poor people’s voices in decision-making processes on groundwater development pathways,” said Taylor.

After a few years of intensive research in Tanzania’s Makutapora well field, scientists have discovered that the well field—which is found in an area mainly characterised by seasonal rivers, vegetation such as acacia shrubs, cactus trees, baobab and others that thrive in dry areas—can only be recharged during extreme floods that can also destroy agricultural crops and even property.

“By the end of the year 2015, we installed river stage gauges to record the amount of water in the streams. Through this, we can monitor an hourly resolution of the river flow and how the water flow is linked to groundwater recharge,” Dr David Seddon, a research scientist whose PhD thesis was based on the Makutapora well field, said.Taylor explains that Makutapora is known for having the longest-known groundwater level record in sub-Saharan Africa.

“A study of the well field over the past 60 years reveals that recharge sustaining the daily pumping of water for use in the city occurs episodically and depends on heavy seasonal rainfall associated with El Niño Southern Oscillation,” Taylor said.

According to Lister Kongola, a retired hydrologist who worked for the government from 1977 to 2012, the demand for water in the nearby capital city of Dodoma has been rising over the years, from 20 million litres in the 1970s, to 30 million litres in the 1980s and to the current 61 million litres.

“With most government offices now relocating from Dar Es Salaam to Dodoma, the establishment of the University of Dodoma, other institutions of higher learning and health institutions, and the emergence of several hotels in the city, the demand is likely going to double in the coming few years,” Kongola said.

The good news, however, is that seasons with El Niño kind of rainfall are predictable. “By anticipating these events, we can seek to amplify them through minimal but strategic engineering interventions that might allow us to actually increase replenishment of the well-field,” said Taylor.

According to Professor Nuhu Hatibu, the East African head of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, irrigation has been the ‘magic’ bullet for improving agricultural productivity all over the world, and “that is exactly what Africa needs to achieve a green revolution.”

The Ethiopian Herald July 16/2019

BY ISAIAH ESIPISU