BY MULUGETA GUDETA

In times long past, Ethiopian writers were isolated from and shunned by society that mostly regarded them as “deranged creatures”, or rebels without a cause, acting and living like narcissistic creatures with big egos pretending to change society or rebel against the established orders. Under the monarchy and later on under the republican regimes, writers were not only targets of social ostracism but also government punishment for daring to speak or write their minds. They were considered rebels whose job is to cause or provoke trouble by agitating the public or organize secret groups that connived to undermine public authority.

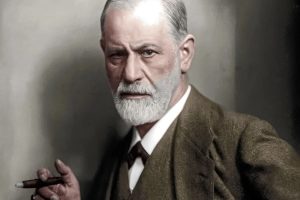

The then prevailing public image of a writer was someone with rough looks, wearing casual clothes, spending time in alehouses or night clubs, getting drunk and speaking politics in public places. The writer was portrayed as living on the margins of society, without fixed address and loitering in the streets carrying a tattered bag or bundles of papers, without caring for their looks or money and living like tramps.

Whatever the stereotype of the typical writer was at that time, there was no denying the fact that writers lived in great poverty as they often had no fixed jobs or incomes as if they preferred the liberties of loneliness, and deprivation over a normal life. That was of course a stereotypical portrait of writers and like any stereotype it was bound to change with times.

Speaking about the lives of Ethiopian writers back in the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s, the late veteran editor, translator and publisher Amare Mammo once said that, “Ethiopian writers live in extreme poverty… They don’t even have the financial means to buy typewriters, let alone modern writing gadgets such as computers. They mostly live from hand to mouth and struggle hard to make ends meet let alone live in luxury”. The late Amare had enough experience and observation to speak about the loves of Ethiopian writers. He personally knew some of them and had truck friendships with others.

Even compared with writers in other parts of Africa, Ethiopian writers are still lagging behind in terms of benefitting or improving their lives from their hard works. They are generally shunned by society and there is no fund or financial support to improve their lives or their writing careers. As a result of this, many of them had abandoned their work early in their careers, without fully tapping their natural gifts. The beneficiaries are mostly people who have nothing to do with the business of writing.

Even if modern writing technology has evolved and spread widely in the last one or two decades, few are writers who can even now buy a laptop or desktop. Still fewer are those who can afford to gather the financial means to publish their works or distribute them outside established channels that are totally controlled by wholesale and retail book traders. In short, the fate of Ethiopian writers more or less remain the same as compared to what it was two or three decades back. Compared with their European and American counterparts, African writers suffer from multiple challenges.

In his book entitled “African Absurdities”, exiled Ethiopian writer Hama Tuma observed that, “As the African writer strives to fulfill his social role both as an objective and committed scribe recording the mores and experiences of the betrayals and epics of the people and also as a teacher and agitator, he or she is confronted by hardships that can hardly be neglected. It is of course essential that not to exaggerate the roles of the writer in a continent where the majority are illiterate, books are expensive and the publishing industry miniscule.”

In addition to material deprivation, writers in Africa, including in Ethiopia suffered greatly from the evil of state censorship that undermined their efforts, distorted their intentions and stifled their imagination. Nowadays, official censorship is legally revoked in Ethiopia. In the past, many writers complained about stifling censorship that they said discouraged them to produce better quality works. Arbitrary state intervention was even worse than pre-publication censorship that stifled any aspiring writer in Ethiopia.

The literary history of Ethiopia has also witnessed the imprisonment and killing of prominent writers like Abe Gubegna and Be’alu Girma who lost their lives in the hands of state security operatives because their works were critical of the regime or because they dared to challenge the authorities. There were also many writers who endured long imprisonment, banishment or even worse situations. It is a paradox of Ethiopian literature that no major works or major writers have appeared after the scrapping of the censorship laws and state repression.

Maybe the “Great Ethiopian Novel” is still in the making maybe because political and historical events have been changing at breakneck speed and writers do not have enough time to reflect and write on these events. Writing surely takes much time of gestation, reflection and actual scribbling before major books appear on the literary scene.

Lifting censorship alone without providing any kind of support to writers who are still engaged in the business of writing is arduous, time consuming and negatively affecting the health of many writers who live in absolute poverty with only their talents and moral strength to turn to. Many have suffered from the frustrations and fears that might accompany their works if at all they are published even under conditions of indirect censorship. They work in fear or self-censorship as democracy in Africa is a fragile promise that often victimizes writers and opinion leaders more than anybody else.

There had been a number of initiatives by the Ethiopian Writers Association (EWA) to help its members publish their works with the cooperation of publishers or printers. There were also plans to improve the livelihoods of Ethiopian writers by providing them with better amenities to create improved working environment so that they can produce better quality works. At one time there was a talk about providing writers with low-cost housing or build residential quarters for them to live in a relatively better comfort.

All these lofty visions by the leaders of EWA who came and went at different times in the past have not so far produced the expected results with the exception that members of the association now enjoy free medical treatment in cooperation with the Black Lion Hospital. Even this is no small achievement given the unbearable medical costs writers might be forced to shoulder whenever they fall ill and have meager financial resources for such emergencies.

One of the challenges Ethiopian writers faced in the past is that they were forced to live and work in complete anonymity without supporting publishers or encouraging critics. They had no contact whatsoever with the book reading public and lacked the opportunity to publicize their works. Understandingly, a handful “elite writers” dominated the literary scene while they were equally victims of deceptions, overt or covert theft and other dubious actions from irresponsible and heartless, deceitful book sellers whose greedy temptations condemned so many defenseless writers to unnecessary sufferings. Whenever some of the more courageous writers managed to publish their works with money they borrowed even from money lenders with exorbitant interest rates.

Official book launching events that started one or two decades back have in some way alleviated the above shortcoming by allowing writers to popularize their works, reach out to their readers and comment on their works while critics also found the opportunity to evaluate new books. Book launching events are also serving as bridges connecting writers with potential publishers although they are very few in number. They also create opportunities for non-professional critics to speak their minds in connection with certain works that often provoke controversies and debates.

These events also attract new writers who used to confine themselves in their houses or in public libraries to come out and see what others are writing or be encouraged to publish their works for the first time. There are many new works that found publishers at those events and become bestsellers simply because they were promoted in public.

Book launching events have also drawbacks in the sense that the works to be presented at such events are not selected by critics or publishers for evaluation. Non-professional “critics often take the floors and comment on certain books in ways that do not promote the writers or their works. There are also allegations that books are reviewed or commented on at these events through mutual acquaintances with the commentators or friends of the authors in question.

This approach is presumably causing bitterness and damage to the morale of writers who work in isolation and have no one to turn to for comments or presentation at book launching events. This is also alleged to be the cause for the proliferation non-professional critics or book reviewers to proliferate simply because they read books and say whatever they like or dislike about the books or the writers in a subjective or arbitrary manner.

However the positive contributions of book launching events are more important than the alleged shortcomings that can be rectified in the long run. In the final analysis the domestic literary scene could have remained dull without these events and writers could not know where to turn to in order to publicize their works. Fewer books could have been published and people who have the ambition to become writers could be intimidated and refrain from publishing their works.

The problem is that this culture of public discussion of literary works is confined to the capital Addis Ababa and to some major towns while most of the remote places learn about these events through the media. Young and aspiring writers and established ones should be encouraged to come forward and discuss books as this is the only sure avenue for producing a generation that will be shaped by knowledge and wisdom and able to articulate the aspirations of the older generation and the country at large.

Cultural bureaus in many regions can and should get involved in this kind of activity instead of focusing exclusively on music and traditional dances while young as well as older people are starving of books, knowledge and the means of spending their free times in a constructive way. Books, libraries and recreational facilities are concentrated in the capital Addis Ababa while remote regions are deprived of these facilities. It may however be time to rectify this imbalance and share the opportunities with people that are so far deprived of these opportunities and facilities.

The promoters of these events should be more extroverts, and their vision should be inclusive and wider in scope. As Chinua Achebe, the godfather of African literature once said about African literature, “every literature must speak of a particular place, evolve out of the necessities of its history past and current and the aspiration and destiny of its people.”.

The Ethiopian Herald December 1/2022