(Selflessly upholding and protecting sovereignty, territorial integrity)

Book Review: By Alem Hailu G/Kristos

Book: Yewetader Lej Negn (I’m a soldier’s daughter/child)

Genre: Poetry/Short Stories (A debut collection of 49 poems/2 short stories)

Page No:120

Price : 100 Birr/$15

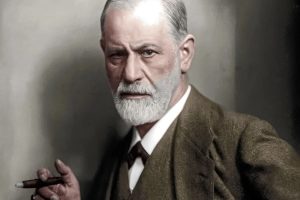

Author-poet: Major/Journalist Woyinhareg Bekele

Published On July 2021(2nd edition) By Berana Printers

In her opening poem Gezot (Exile) Major/Journalist/Author-Poet Woyinhareg Bekele notes that even if the slavish is unchained to let himself free he mongers to servitude tied down by vengeance. In bad shape and from force of habit, he is unable to unshackle himself from hatred.

Presumably in this poem she lambasts members of the terrorist-dabbed TPLF and Oneg Shene engaged in killing spree of innocent civilians. Even if given a chance to mend their evil bent they had pressed ahead with their evil agenda to the extent of being dubbed terrorists by the parliament. The two extremist wings spliced in marriage do so obsessed by the secessionist and divisive agendas of opportunist westerners exhibiting revolting lust to colonize the mind of Africans creating and fomenting antipathy along ethnic and religious lines.

In her descriptive poem Lanchiw new (It is just for you) the poet narrates the priceless sacrifices a solider pays for the furtherance of his nation. In word pictures the poet draws attention to how a solider divorced from sleep see to the tranquility of his nation. When a solider standstill he may face a grill underneath and when he gazes up he suffers a scorching sun bearing down on him not to mention the razor-sharp and bone-chilling cold that awaits him late at night.

Passing through the roller-coaster of the aforementioned feelings, a soldier never forgets to put his nation in the cherished corner of his heart. When he is martyred killing enemies it is with pining eyes his gazes at his beloved flag that hovers high.

Trekking rocky roads punctuated by twigs he has to jump from one cliff to another, while at the corner a roaring river to cross or a rolling mountain to climb waits in lay for him.

Consummating the acid-test nature poses on him with success, lighting the darkness, palisading borders with his bones and watering the flag with his blood, a soldier is one who is pursuing monasticism for the wellbeing of his country estranged from his parents, siblings and children.

When seen through the prism of impartiality, nation’s sovereignty bears soldiers’ footprint, sweat and blood, the poet relates, adding, true to his oath, a soldier effectively sees to his entrusted-duties.

In her short poem Nigerwat (Tell her) the poet encapsulates a deceased soldier’s behest. He asks the living to tell motherland a soldier’s best wish of wellbeing for her lingers even after he crossed the river of death.

In the poem Kekedahegn Kehedet Yilek (Worse than your betrayal) using a woman solider as a persona the poet exposes a tainted trust by a fellow soldier with whom she exchanged romantic feelings far from parochialism at moments they got a relief from the arduous condition characterizing a military life.

In the aforementioned poem the poet relates about a woman solider deployed in the northern command from where a solider she befriended hailed. Unencumbered by language they were enjoying a romantic bliss. She was paying a visit to his mother’s home. Oneness was permeating the air. Yet making a 180 degree turn this love partner of hers partook in the stab in the back the terrorist TPLF carried out against Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF’s) northern Command.

What the persona found incomprehensible is not the betrayal of a love partner but how a solider commits a treason attacking fellow border-defenders off guard? Worse still, how he denies them a proper burial exposing their bodies to vultures. “How failed I to unmask you then?” she introspects.

In another poem Hager Setugen (Give me a country) she mocks the narrow-minded that uphold parochialisms which aims at sizing down a nation to abodes as narrow as their outlook. With a figurative speech she tells them that as a yolk is nothing out of its shell she is like a fish out of its elements without Ethiopia (motherland). “If you have a dreg of national sentiment, give to me Ma Ethiopia so that my body lies to rest on her black soil,” she rebukes such guys.

Unless one turns God-bestowed or nurtured talent to practical use it is nothing different from burying an asset, she notes so in her poem Web Ejoche (Superb hands) alluding to the biblical preaching about talent. Here she notes the significance of coming up with a brainchild—book— like I’m a soldier’s daughter.

Apart from the global peace keeping missions, zeroing in on discussions and deploying soldiers, peace brokers better consult mother earth about what(the landmines) it carries in its belly, the poet advises in her poem entitled Selamn Felega ( The pursuit of peace).

In another poem Fikre Yizogn Enji (it is for love of labor/had it not been for love) she portrays how a solider pays selfless sacrifice not returning back home even on holidays.

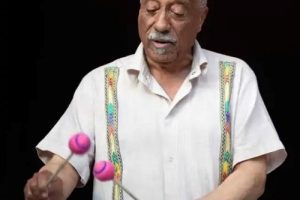

Many are those who want to be friends or endear themselves when one is not short of money but a true friend is one who is there when one is in need. There is also a saying your friend is your fulfilled wish. Author-poet Woyinharge puts a spotlight on this fact drawing attention to how soldiers in a battlefield compassionately exchange a cup of water. She portrays how a soldier hauls a wounded solider to safety and a dead one to a proper burial ground. This poem entitled Yameral (It is beautiful) foregrounds friendship against the backdrop of a military life.

In her poem Yewetader Lej Negne (I’m a soldier’s daughter (child)) the poet indicates that before her eyes her father appears as her country, while her country as her soul. That is why she feels an excruciating pain when she hears her country has encountered harm. Reverting back to her childhood, she notes how she began to twist her tongue uttering the sweet word Ethiopia and how she is imbued with a national feeling from early childhood. “Ethiopia is no joking matter to me,” she notes.

As the author-poet indicated in the preface of “I’m a soldier’s daughter’

“…as a soldier’s daughter whose father was heroically martyred at Kara Mara during the Ethio-Somalia war and as such a half-orphan brought up by a single mother who had to work her fingers to the bone undaunted by all odds,” Major Woyinhareg knows soldiers life inside out.

Later upon joining the Ethiopian National Defense Force inspired by her father’s valorous deed, she has a firsthand knowledge about a soldier’s life and that of his wife and children. These experiences and intimate knowledge have afforded her to come up with a book that proffers a peck to readers regarding the life of army members. She uncovers a life strange to many. The bitter sweet expression that a soldier’s daughter does not expect her dad at her wedding and graduation but she will be consoled by the flag decorating the room is so expressive of the case in point.

As commented on the Blurb by Dr. Commander Demelash Kassaye the book conveys key messages in an entertaining and sometimes ironic manner. The book whose themes are drawn from practical experience shows the role of a soldier is unmatched for the furtherance of a great nation like Ethiopia.

The themes of most of the poems ‘being a soldier is a most important and significant task’ is not only timely for Ethiopia, beset by challenges, but it is also of a universal one.

The major segment of her poems are crafted in art for life’s sake style—conveying messages such as national feeling and soldier’s life— while a few are shaped in art for art sake— like reading love from a timid lover’s eyes and motherhood . “As my mother still carries me in her mind—worries about me— I am not yet born as a fetus carried in a mother’s womb,” the poet says. This fact has become all the more apparent to her upon giving birth herself.

Another poem Altegenagnetom (Disconnected) reveals a spouse’s secret. Though their fingers are tied one by a ring their words are discordant.

The rhythm and rhyme of her poems with picturesque words renders her poems appealing to the ear. Allusion in page 13 on (Take super hands about talents; Mathewes 25:14-30)) parallelism (Had it not been page 14) and simile (I’m just like a yolk, page 11), among others, are the palatable garnishes to the poetic dish she arrayed. She is capable of writing poems of different lengths and styles. Obviously, with the passage of time, practice and reading she could take her talent to yet another height.

Once more from her short stories I have noticed her ability of penning stories packed with social messages—a soldier’s life, love with a solider before whose devotions come duty to the nation, keeping promises even if pushed to the end of one’s patience, perseverance and mental health.

From the way she crafted the setting, used characterization, employed ample dialogue, adopted flash backs to defamiliarize plot, created conflicts with resolution it is clear that she knows well how to make her stories immersive.

Her book reminded me of the literary pieces of Maxim Gorky the figure head of socialist realism.

I bow out recommending her to read his book and you her book.

The Ethiopian Herald November 3/2022