Cross-border trade (CBT) plays a vital role in improving the livelihoods of people living in border areas. It is a source of income and employment for a large number of people. In the Ethiopian context, CBT allows border communities, predominantly pastoralists, to have an access to basic consumer goods and increases food security.

It also often fosters peaceful social relations and cultural understanding among trading communities along the borders. With its growing economy and as one of the largest land-locked countries in the world, Ethiopia in recent years has shown a strong interest in developing long-distance trading and transport corridors.

The country has invested heavily on multiple projects that would interconnect her with its neighbors via road, rail, air, telecommunications and power lines. A research paper conducted by researcher Hannah Elliot and her partners, and published by Forum for Social Studies concluded that as the country’s economy has expanded over recent years so has its ambition to diversify its trade outlets to the sea, which at the moment largely depend on the Port of Djibouti.

Ethiopia’s government decision in 2016 to invest on the development of the Berbera Port, signing an agreement with Somaliland and multinational ports operator called DP World and thereby ensuring a19 Percent stake in it, is part of Ethiopia’s ambition, so says the paper.

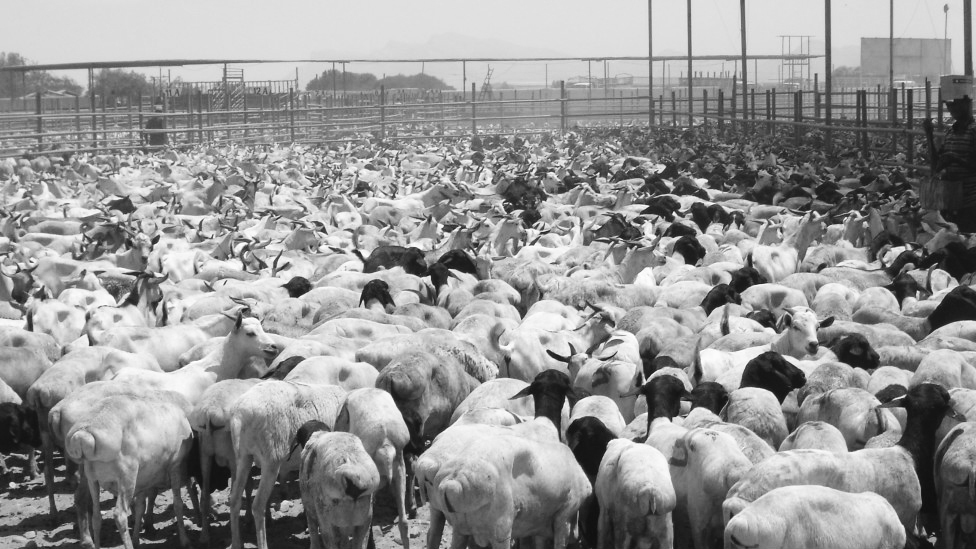

The paper further remarked that by investing in trade corridors, the Ethiopian government also hopes to gain more control over the lucrative livestock trade in the Arab Peninsula by making it more formalized. While much of the livestock exported by Somaliland and Djibouti to the Middle Eastern countries are sourced from Ethiopia, the livestock trade on the Ethiopian side has largely been remained informal.

“Developing CBT corridors has implications for the local communities and traders doing business in the already established trade corridors, which tend to be characterized by ethnic and trans-ethnic networks, official and unofficial authorities and formal and informal norms. On the one hand, the development of trade corridors promises the integration of formerly remote and marginalized border regions with political and economic centers,” indicated the research.

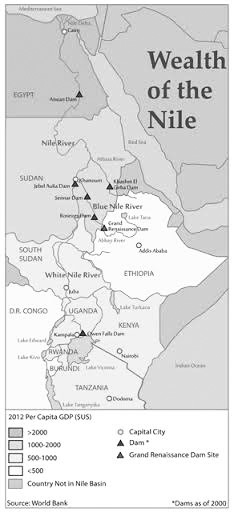

CBT is undertaken in US dollars with letters of credit and is regulated by the governments of the trading countries and revenue is extracted from the traded goods. According to data from the National Bank of Ethiopia, formal cross-border export trade to neighboring countries Kenya, Djibouti and Somalia (including self-declared independent states like Somaliland) between 2010 and 2017 amounted to about 2.7 billion USD.

Formally exported commodities, according to the same data, were dominated by fruits and vegetables (which accounted to 65%), followed by live animals (25.56 Percent) and khat (6.28 Percent). More than 90 Percent of Ethiopia’s formally exported goods go to Somalia.

Informal CBT is one factor for escalating rate of informal cross border trade. Because informal CBT is movement of goods in which all or part of the trading activity is unrecorded or unrecognized by the government, and without adherence to procedural requirements of all formal institutions. Volumes and values of informal cross-border import and export can be gauged by examining seized contraband items.

According to the Ethiopia Revenues and Customs Authority (ERCA), the total value of seized export contraband from Ethiopia in 2014/2015 was 2.01 million USD, while in 2016/17 it reached 6.7million USD. The Berbera corridor is one of the most important corridors for export contraband, with significant amounts of contraband passing through Jigjiga where live animals, cereals and Khat dominate the export contraband. In 2014/15, the total value of seized contraband import to Ethiopia was USD 20.9 and it reached to 36.2 million USD in 2016/17.

Concerning the impact of Berbera gate, the finding of the research paper indicated that the Berbera corridor is an important gateway for informal imports from the Somaliland into the Ethiopian hinterland, import dominated by clothes, electronics and foodstuffs. Actual amounts of informal trade are much higher than the estimates provided by seized contraband figures.

Regarding the incapability of the government in tacking out informal cross border trade, the research paper noted that the government of Ethiopia has increasingly moved towards formalizing livestock CBT; and among the measures taken to promote formal trade is the establishment of quarantine services. For instance, in 2010, the federal government began the construction of a quarantine center in Jigjiga, though the centre still remains unfinished. The government expanded the number of official custom points in the Somali Regional State.

Accordingly, five new custom points were established at Togwajalle, Harshin, Hartasheikh, Daror and Gashamo intended to encourage traders to use formal channels. However, due to lack of capacity they largely became facilities to police and control livestock leaving Ethiopia for Somaliland. In order to reduce the alarming rate of informal cross border trade, the paper pointed out that the government should be more forthcoming in terms of keeping the public informed about the country’s role and investment in the Berbera corridor and port.

This will ensure that traders are informed of the changes that these investments and infrastructures will bring about. Transparency on corridor development and engagement with the relevant stakeholders will help to mitigate suspicion and mistrust. Adding the study paper highlighted that the governments of Ethiopia and the Somaliland as well as DP World should ensure that municipal authorities have a stake in trade corridors, including vis-à- vis key infrastructure such as ports, roads, railways and customs posts. Moreover, it is important to consider ways that would ensure that small-scale traders and logistic/transport and other service providers participate in and benefit from the development of the Berbera corridor.

As a note of advice to the government of Ethiopia, the study indicated that the government should develop policies to support pastoralists living in border areas so that they are not harmed by formalization policies.

These could include allowing free market access, providing information systems on livestock marketing, providing livestock insurance, and developing livestock export framework that protects small scale traders from large-scale entrepreneurs.

Moreover, the government should update its Petty Periphery Trade policy so as to support small scale traders and border communities. Specifically, the government should update the now outdated list of commodities that can be traded tax-free in border areas and the prices these commodities can fetch as well as reconsidering the monetary limit that is placed on petty traders which is currently overly restrictive.

It should also consider increasing the number of frequencies that petty traders are permitted per month to enter a neighboring country for purposes of trade. Finally, the government should prioritize the policy’s implementation, investing in increasing the capacity of custom points, including with the appropriate technology, so that they are able to support formal trade rather than simply police informal trade.

The government should prioritize for the completion of the quarantine center at Jigjiga and pursue accreditation with the Mille standard as with centers quarantining livestock destined for export via Djibouti. This will ensure that Ethiopian livestock formally exported via Berbera and Bosaso will be accepted by livestock -importing states.

The Ethiopian Herald March 31, 2019

BY MEHARI BEYENE