Today, Marks the eve of Adwa victory, a victory of the weaker, and the just, over the stronger and the unjust.

After a long tactic of waiting from the Ethiopian and Italian sides in Adwa, the wrong information Oreste Baratieri relied on, supplied by double agents—Basha Awalom and Balambaras Gebregziabher—buoyed his confidence to take an offensive against the Ethiopians.

The military and intelligence strategies of ancestors stood taller than that of the Italians, eventually putting the magnificent victory in store. Subsequent pan Africanists and freedom fighters took inspirations from the victory.

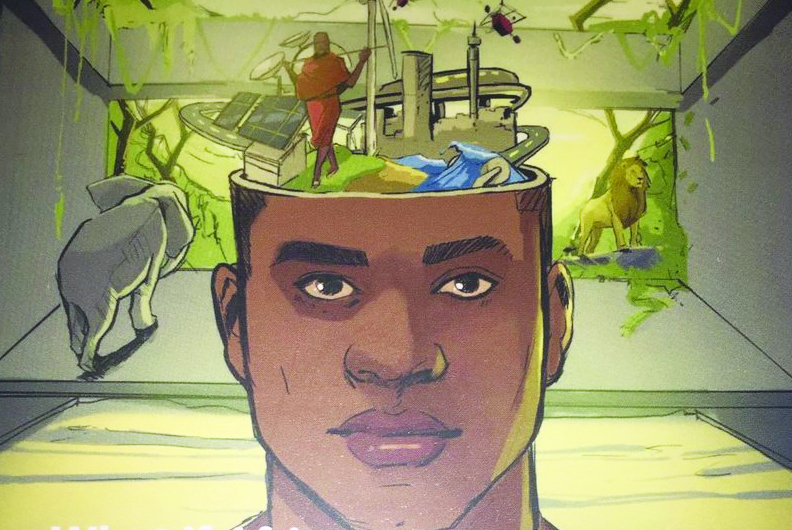

Africa today has “politically independent states”. However, the peoples’ rich institutions are far from being harnessed. BIRUK SHEWADEG, a Ph.D candidate at the Center for African and Oriental Studies of the Addis Ababa University challenges the long entrenched epistemic hegemony of the West. Excerpts: Afrocentric epistemology implies an inquiry that seeks to escape from Eurocentric hegemony of knowledge production in combination with a search for an authentic Africanepisteme.

The assumption is that mainstream organizational theories in the social sciences and humanities to be bare reflections of the conceptual framework of Western ideology and thought that negates worldview of the Africans, which in the process ‘deexoticize’ Africa and ‘banalize’ it.

The collective European subjectivity has dominated the ‘normative’ episteme in the academia that illegitimately amounts to an objective status for all humanities proper.

Thus, this writer situates rethinking of such an epistemic construction as an imperative. Cognizant of the limitations and partiality of all knowledge and a vigorous need for studying Africa in its own ‘specificity’ as Mamdani (1996) might avers, I also argues that Afrocentric epistemology is one legitimate way of knowing about our world. The epistemology discussed in this article is premised in the centricity of the Africans within the context of their own cultural experiences. The discourse, to which I argue here, ought to promise redemption that aims to re-problematize explanations of phenomenon related to Africa away from Eurocentric attitudes and conceptual frameworks.

Emancipation of the discourse, the writer avers rests on its pragmatic adjustment to black disorientation, decenteredness, and lack of agency via epistemic anarchy or the ‘Fanonian violence’. While stressing in a quest for an Afrocentric epistemology, the writer also asserts in a great deal of Ngugi’s concern about the language factor in Afrocentric discourse.

As per my understanding, unless the African vernacular assumes due recognition with respect to developing an Afrocentric epistemology, disenchantment of the discourse is inevitable. “Placing African ideals at the Centre of any analysis that involves African culture and behavior” is Asante’s (1987:6) understanding of the very idea of Afrocentrism.

He presented it as a discourse that fundamentally seeks to uncover and use paradigms that may reinforce the centrality of the African ideal as a valid reference for acquiring and examining knowledge. In an attempt of re-valorizing the African place in the interpretation of Africans, the Afrocentric discourse Milam argues, challenge the “foundations that Eurocentrism is grounded in explaining Africa” (1992:12).

As a framework from which the world is approached from an African perspective, Afrocentrism puts the people and culture of Africa as the general focus that represents an African world view. Afrocentrism begins its analysis with the assumption that Eurocentrism has destroyed African culture; deAfricanized the consciousness of blacks, and crippled their economic and cultural development (Asante 1991).Thus, it seeks a solution which may include strengthening the development of an Afrocentric epistemology and making Africa one foundation in generating knowledge.

This knowledge would ultimately become emancipatory and a defensive weapon against a pervasive and domineering Eurocentric worldview. Afrocentrism, as a philosophy that affirms blacks as an “active historical agents”- is vital in reversing a perennial misrepresentation of African history and culture and in enhancing self-esteem.

This makes the discourse in need of a vigorous contention against European sole hegemony in knowledge generation, and offering Africans an ennobling, short of however ‘exaggerated’ and ‘mythologized’ versions of reconstructing the African past. In such a way Afrocentrism requires an absolute abolition of the West from the center of African reality (Asante, 1988). As a paradigm, Afrocentrism enthrones the centrality of the African as expressed in the proper forms of African culture, and activates consciousness as a functional aspect of any revolutionary approach to phenomena. It addresses how the unbalanced relation since 15th Century that is where the West has started its contact with the continent thereof, has resulted in a unidirectional narrative of human history.

It questions how the West sought to assume the right to tell its own stories and others solely from its own vantage point. It challenges the overall Western monopoly in knowledge production which unmasks the undeclared assumption that only the West is legitimate in producing and disseminating its produced knowledge. As it is an experience from a certain segment of humanity, Afrocentrism challenges the universal pretension of the Western epistemology to be incomplete and often distort when it comes to problematize others’ phenomenon.

By virtue of its call for an Afrocentric epistemology, Afrocentrism counters this with the assertion of legitimacy of African ideals, values and experiences as a valid frame of reference in pursuant of an intellectual inquiry.

It is important, however, to note that Afrocentrism does not represent the other replica of Eurocentrism- total claimant of control over the monopoly of knowledge. It rather seeks to mature relationship to other cultures, neither imposing nor seeking to advance its own material advantage. Here, an epistemic critique may arise on the issue of relativizing knowledge. It only strives for centering African culture and claiming it as a valuable part of humanity that attempts to fulfill Africans role as a legitimate partner in a multicultural discourse- something constructed together.

It only seeks to broaden the horizon of knowledge production. Generally speaking, Afrocentrism as Asante noted, adhere to the idea that “… all people have a perspective which stems from their centers … while Eurocentrism imposes itself as universal, Afrocentrism demonstrate that it’s only one way to view the world”(1988:87).

This make the justification of knowledge claims to be within the context of knowledge whereby the knowledge is made. Therefore, it is not only senseless, but would “yield no results to find justification for a claim made in one cultural context in another as the standards of both contexts may be incomparable‟ (Jimoh& Thomas, 2015:5).

The domain of knowledge in African epistemology is not polarized between the doubts that assail epistemic claims and the certitude that assures our claim. As per the claims of Afrocentric epistemology is concerned, Culture plays a vital role in the cognitive understanding of reality and as Brown (2004) argues “unless one is intimately familiar with the ontological commitment of a culture, it’s often difficult to appreciate or otherwise understand those commitments.” Thus, understanding the African cultural and ontological conception of reality is crucial to enable us understand the African approach to knowledge. Furthermore, for the African, there is more to reality than what is within the realm of empirical inquiry.

The Afrocentric epistemology asserts both that the African distinct cultural values, traditions, mythology, and history has to be considered as a body of knowledge that deals with the social world; and that it is an alternative, nonexclusionary, and non-hegemonic system of knowledge based up on the African experience.

It investigates and understands phenomena from a perspective grounded in African centered worldviews. Afrocentric epistemology is about a critique of systems of ‘educational texts, mainstream academic knowledge, and scholarship; and further validates the African experience and ontology.’

Afro-centric epistemology, generally speaking, calls for an alternative culture to be part of the school system and knowledge.

A society’s worldview, in view of Afrocentric discourse, determines what constitute a problem for them and how they address it. As a result, Afro-centric scholarship reflects the “ontology, cosmology, axiology, and aesthetic of the Africans” (Mazama 2001:14). It is with this assumption that it has to be centered in the African experience.

Frantz Fanon’s idea of liberation appears vital in this regard. As with liberation from mental colonization, there must be a transformation of the status quo as to find a foundation for incorporating alternative perspectives. This is indeed moral and profoundly political.

One must take in to account the point that this process of intellectual liberation is a response to the slavery, colonialism, and imperialism since 15th century. Alternative voices are vehicles for liberating for those who demean thereof.

Ngugi’s concerns with the preservation of the vernaculars and cultures are persuasive in that identity is clearly embedded in our language and culture and therefore be kept lingua Franca in the academia is worthwhile. For a full-fledged Afrocentric epistemology without the use of African vernacular is not only obsolete but also inconceivable.

The Ethiopian Herald March 1, 2019

BY BIRUK SHEWADEG