Ethiopia’s aspiration of transforming its economy has a long history that dates us back to the launch of the First Five Year Plan (1957-1961) and the series of five year national development plans and strategies that followed it. Most of these national plans and strategies of the Imperial, Socialist and post 1991 governments such as the Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction Program (SDPRP), Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP), Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) I including the latest Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) II have emphasized on modernizing the manufacturing sector and agricultural commercialization. The programs, however, had energy challenges impeding the realization of the programs. Hence, the aspired social-wellbeing has become a far-fetched goal.

The question is: ‘Why does a century-old planning and investment fail to materialize into ensuring food security to Ethiopians?’shall be left for further investigation. However, energy shortage to supply the needed power and run industries in the manufacturing sector remained a major challenge. In addition, favoring foreign investors to meet the demands for foreign currency diverted attention from efforts to promote small-scale local industries.

The results indicate less value addition from foreign investments to the country’s manufacturing sector despite the provision of incentives including tax holidays. In a challenging COVID-19 period like now, most hospitals in Ethiopia have no resources to provide lifesaving treatments and lack ventilators, if any, such services are doomed to fail easily due to problems associated to constant and reliable energy supply.

Without enough energy, all national plans and investments cannot go beyond being paper tiger initiatives and bring no economic return to improve lives of people. In addition to challenges to providing quality health care services, ensuring food security is a prerequisite to building a healthy society. Hence, food security continued to stand at the core of government agenda and achieving it requires water, irrigable land, technology and energy for a better output.

In order to maximize the productivity of their agricultural sector and fulfill the food demands of their people, Sudan and Egypt irrigate a tract of land more than five million hectares using Nile. Furthermore, Egypt diverts water from Lake Nasser to irrigate land outside of the basin while the remaining basin countries, despite their irrigation potentials, have so far been less than a fifth of the land that Egypt and Sudan developed. Unlike Egypt, Sudan has clearly aligned its position in line with the Nile River Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement and subsequently recognized basin counties’ right to mutually benefit from the Nile water.

This exemplary action is a commending work in progress to reinforce the foundation for regional cooperation and development in the basin. The Ethiopian Government, in this regard, made meaningful contributions through working to bring a resolve to the no war-no peace relationship with Eritrea; successfully mediating the peace talk in Sudan; and negotiating a power sharing agreement between Salva Kiir and Riek Machar in South Sudan and sending troops to Somalia to stabilize the region. These efforts could have been enough to tell Egypt that Ethiopia and Ethiopians are peace loving and considerate to build prosperous future to the people in the Nile basin.

This commitment from Ethiopia is a manifestation of its firm principle to adhere to provisions of the Cooperative Framework Agreement that requested Nile Basin States to observe the rules and procedures as established by the Nile River Basin Commission to facilitate the effective implementation of equitable and reasonable utilization of the Nile water. Ethiopia, contrary to Egypt’s propaganda, is not rushing to build its economy at the expense of Egypt and our long-lived friendship. It is just struggling to achieve a lower middleincome status in five years from now.

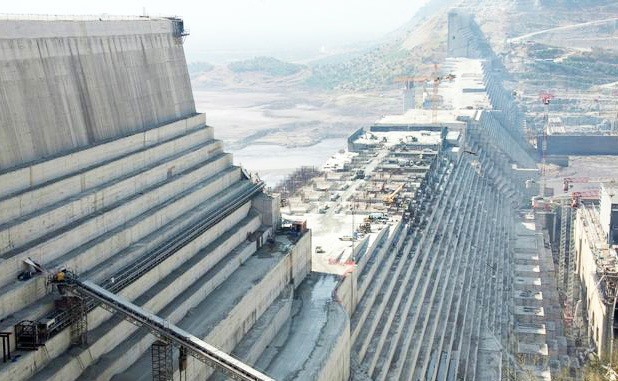

In order to attain this goal, Ethiopia requires to take poverty reduction measures that rely on sustainable economic growth. This requires an informed visionary government that introduces the right policies and a disciplined productive work force to implement the strategies. A political leadership and committed workforce alone cannot guarantee a sprint into middle income status and bring the desired growth. Achieving the middle-income status requires investments to improve the capacity of the manufacturing sector to produce ready made products to cater for local and export market demands. This helps the country attract foreign direct investment, increase its trade competitiveness, reduce trade deficits and raises per capita income and leads to human development in the end. Hence, energy becomes the necessity and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam’s role in generating hydroelectric power to feed the industries and diversify income generation options becomes crucial. The energy will support revival of agricultural and agro[pastoral] livelihoods around the dam and countrywide through the creation of employment opportunities and promotion of water based eco-tourism, irrigation and fishery activities.

More importantly, it contributes much to meeting the power requirements of huge electricity intensive infrastructures in neighboring countries bringing home both economic and public diplomacy returns to Ethiopia. The construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam necessities putting in place energy intensive policies and building institutions that are targeted for Ethiopia to leapfrog into an investment and trade hub in the region.

The generation of energy alone, however, should not be an end goal of such a massive project. The management of the energy produced, and the introduction of high-tech industrial plants shall be forward and backward linked with Ethiopia’s vast agricultural and productive work force potential. Beyond being mere energy export plans, the strategic direction lines should target attracting foreign direct investment from the manufacturing and service sectors to enhance our financial self-reliance.

This will significantly contribute to Ethiopia’s capacity to finance its own development and reduce trade deficits. Doing so positively influences our political bargaining power. Through widening our political space globally, it will increase our ability to pay for homegrown initiatives that have ripple effects in the region. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is a project that Egypt should not have hesitated to support. Egypt would have seen benefits from the power generation without hustling and bustling to invest in other dam building projects.

It will only require Egypt to be interconnected to the power grid from Ethiopia to meet its future demands for energy. While inviting Egypt to choose to decide to be connected to the power grid, Ethiopia takes into account the genuine concerns of our sisters and brothers in Cairo over the filling of the dam and the impact it might bring over the regular water flow of the Nile River. It was to this end that the Ethiopian government has shown a considerate position by agreeing to extend the filling time of the dam to seven years, a time it takes a kid to grow and start grade classes. Ethiopia has never translated temporary political differences among Nile basin states into hostilities. It rather respects their effort to secure their positions and interests as far as it does not harm its right to develop Nile.

Since the inception of the dam, Ethiopia has consistently called for concerned basin countries to appropriately participate in the planning and implementation processes of the project in a show of its due respect to the principles of subsidiarity within the context of observing the basin-wide framework. The matter, however, went into whoever that has lived year-around expecting to feed on a milk from someone’s cow in the upstream failing to invest to make the meadows green while waiting foolishly the owner of the cow to continue to be happy to offer the milk.

In a similar story, Egypt failed to refrain from the sky is falling down rhetoric and continued to misinform the world against our intentions to keep the basin well fed by sharing a cow. The Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is the Habesha cow Ethiopians put to sacrifice for a common growth. The energy to be produced is the milk to keep all of us in the Nile basin strong and healthy. Egypt, however, is making a very colonial discursive attempt that harms a constructive discourse between the basin countries. Such a path only consumes time and smears mud on the rights based cooperative face Ethiopia entertains currently on the project matter. Capitalizing on the cooperative spirit and pleasing the owner of the cow have to be the way forward for all Nile basin countries to maximize their benefits legitimately. As clearly stipulated in the Cooperative Framework Agreement, all Nile Basin counties shall formulate scientific strategies to conduct watershed management activities in their respective jurisdictions to control destruction of forest ecosystems and mitigate potential adverse impacts from climate change to maintain a steady supply and flow of Nile water in the basin.

The cow gives milk only when the meadows have enough grass and the villagers upstream at peace with each other and the cow’s owner. Egypt, apart from resisting the development needs of basin countries shall correct its uncooperative behavior and divert its resources from sponsoring destabilizing projects to supporting tree planting and energy saving initiatives in water source countries.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on Nile is a done-deal project and upcoming deliberations shall focus on setting the agenda on how the energy produced from the dam shall be distributed among basin countries to meet their development needs and demands, which is milking and producing the cheese out of it. Egypt since the time of the pharaohs, however, has been possessed by an evil that adores conflict, aggregation, greed, selfcult building and sick hegemony seeking behavior.

And I understand that exorcising such an old pharaonic evil requires patience, spiritual maturity and calmness and that is what Ethiopia is responsibly exhibiting. I firmly believe that the blessed lake the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam forms will hold a holy water to cleanse and scare away such an evil. I still believe that the dam heralds Egypt’s coming into its being to reconcile its differences and feast with us from the same common plate. The Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on Nile is not an evil dispenser.

It rather is a living statue that paves the way for a shared survival in the Nile basin. Ed.’s note: Samuel Tefera Alemu (PhD) is an Assistant Professor at the Cent er for African and Oriental Studies and Associate Dean for Research and Technology Transfer, College of Social Sciences, Addis Ababa University He is reachable through: samuel.tefera@aau.edu.et

The Ethiopian Herald April 10/2020

BY SAMUEL TEFERA ALEMU (PhD)