In any given society, under normal circumstances, water is an integral and essential part of the whole ecosystem. But when water flows downstream, in the form of flood, it can cause various types of damages including land degradation and soil erosion; disturb the physical and human environments balance; and even cause conflicts among community residents.

All these negative effects result from lack of a well-devised and sustainable land-use plan based on an ethical and moral-based costs and mutual water-sharing systems. Recently, although Ethiopia has made commendable efforts to construct dams, it has had little or no capacity to turn its fresh water resources coming from her 12 major rivers for its agricultural progress and hydroelectric power installations.

On top of these shortfalls, Ethiopia was unable to prevent her rivers from carrying away its valuable alluvial top soils beyond its borders.

Although the Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin remains rich in its fresh water resources that are suitable both for agricultural reforms and human settlements (in the water source region) much of the basin areas have been affected by drought. Similarly, irrigation schemes in the lower riparian countries have usually been affected by high dam sedimentation issues. The causes of these negative results are associated with lack of utilizing a sustainable land and water-shade management system coupled with rapid population growth in the region.

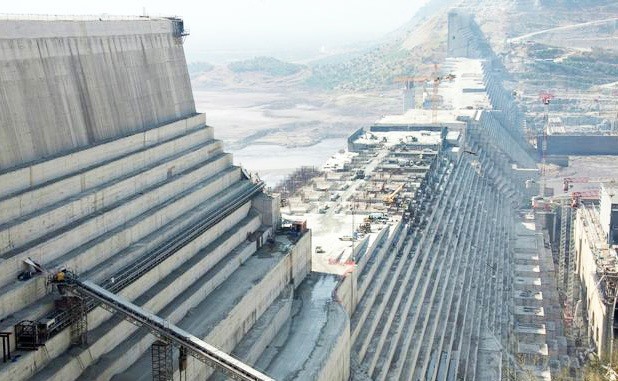

Most recent studies about the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) conclude that, in order to prevent the ongoing sedimentation problems, maintain food, nutrition, and regional environmental security for the entire population in the three countries, there is a very urgent need for making a genuine regional co-operation and swiftly put into practice a conservation-based sustainable development plan.

Ethiopia owns twelve major river basins among which, the most densely inhabited and important basin in Ethiopia is the Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin. It covers 198,500 square kilometers and its annual water discharge amounts to 50 cubic kilo meters. The Basin contributes about 45 percent of Ethiopia’s surface water resources, sustains 30 percent of the population, 20 percent of the landmass, 40 percent of the national agricultural production. The Basin holds most of Ethiopia’s hydropower and irrigation potential. In fact, nearly 85 percent of the total annual water discharges of the Upper Nile come from the Basin; while the remaining 15 percent of water discharges come from the East African tributaries of the White Nile.

In this article, I would like to discuss and highlight the importance of planning and implementing a conservation-based sustainable irrigation agricultural schemes based on genuine cooperation agreement made by the upper and lower riparian countries.

Given that the Abay Basin is one of the most environmentally degraded regions in the African continent, the Basin requires: (a) much deeper understanding of the various environmental problems intertwined within it; and (b) the need for cooperation to rehabilitate the water borne resources. Such actions help

the plan to complete the ongoing GERD construction in timely fashion for the common use of the three countries depending on the Basin.

Environmental Stress

Within the upper Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin coverage area in Ethiopia, there live virtually 10 ethnic groups, mainly as oxen-tilling farmers, slash and burn cultivators, cattle herding pastoralists, fishermen and the like, who practically depend on urban-based resources for their livelihoods.

In areas endowed with alluvial soil, Ethiopian farmers cultivate two crops within a year. Plus perennial crop farming is practiced here as well. During the dry season, the pastoralists inhabiting the lowlands of Ethiopia move with their cattle in search of water along the tributaries of the Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin. These seasonal movements by pastoralists usually create conflicts arising from both land- and water use rights. Particularly along the Abay-gorge, caused by severe deforestation, most wild animals seek refuge elsewhere.

Although the Tis-Issat-Falls (located near Bahir Dar City) currently provides hydro-electric power to some towns nearby, there exists no large-scale dams, to date. Due to mainly financial and geo-political reasons, Ethiopia has not been able to benefit from its God-given water resources in this region. In fact, its delay contributes to the poor development and luck of electricity power to inhabitants living within the upper Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin.

While Sudan is thankful and cooperative for its benefits from the Basin resources, Egypt is suspicious of the plan to complete GERD, as the Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin is its most important life-line. Without water and indispensible soil nutrients from the Basin, the civilization of Egypt would have not been possible.

Yet, soil research findings indicate that the present soils in Egypt are poor in nitrogen, iron, zinc and magnesium contents. Due to deficiency in these micronutrients, the color of plants has changed over the last 40 years. At the same time, as a result of population increases (about 3% per year) and soil degradation, large areas of land in Egypt have been reclaimed.

Besides, the water’s seepage, salinity, sedimentation levels and high evaporation (2 km³/year) have all reduced the farm production in Egypt by more than 15 percent on average per year. At the moment, in order to feed its rapidly growing population, Egypt requires more water and nutrients/fine silts/ in its farm soils; especially in its recently reclaimed lands. However, mainly due to sediment loads accumulating in the Aswan High Dam in Egypt, because it receives little volume of water coming from the White Nile, and since there is lack of annual deposition of Nile alluvium in the Basin’s water flow, these demands in Egypt cannot be adequately met.

Therefore, it has been suggested that the Rosaries of the Sennar and the Merowe Dams in Sudan plus the Aswan High Dam in Egypt require basically enhancing and expanding the natural vegetation patterns within Ethiopia. In turn, this action may assist the region to harvest sustainable annual rainfalls and further reduce the flow of silt-flood-water leaving Ethiopia.

The poor and negative changes existing in managing the natural vegetation cover patterns result mainly from the land degradation processes taking place along the upper Abay Basin, which usually leads to unexpected abnormal floods occurring seasonally, reducing the soil nutrients of both the upper and lower riparian regions. That means, such mismanagement of natural resources may change, not only the physical environment, at least the regional scale, but also, it affects negatively ordinary peoples’ life-styles.

The root causes for such resource mismanagement include, but not limited to, (a) lack of well devised land-use planning, (b) rapid urban and rural population growth, and (c) poor farm production performances. In order to feed themselves and the growing urban population, the farming communities of the upper Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin are more and more forced to exploit and encroach the natural resources in their habitats.

Besides, due to lack of alternative energy sources, locally available building materials, etc., the entire rural population living within the Basin depends on locally growing trees and grasses. That means the negative Vegetation depletion in highland Ethiopia has had a profound blow on the physical and human environments in the region as well as in the two lower riparian countries (Egypt and Sudan).

The dilemma here is that, in spite of the fact that Ethiopia is prone to drought and food shortages and without any rural electrification program, Ethiopia remained unable to divert its water resources from the Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin for either agricultural and/or human settlement and electrification purposes.

Attributable to this dilemma are mainly: (a) its financial constraints, (b) its political instability within the country and (c) the threat exerted by Egypt to prevent any plan of building dams and other large-scale irrigation projects in the Basin areas. Hence, Ethiopia was held aback from constructing any tangible hydroelectric power installations within its own entity.

Be what come may, rural electrification would save a lot of the trees that are presently fused for heating and for cooking purposes, which has led to severe deforestation activities in Ethiopia in general and in the Abay River Basin tracts in particular.

In my view, re-forestation programs can be implemented successfully only when alternative energy sources are provided to rural households at the same time. To reverse this situation, since the 1970s, a nation-wide re-forestation program has been introduced and consistently maintained; yet, this action did not bring any significant change within the Upper Abay River Basin.

The barren land could be re-vegetated quickly since the basin has sufficient rainfalls (1224 mm annually) and a favorable climate and soil condition (mainly consisting of Vertisols, Nitosols and Alluvial soils). If done properly, reforestation program will increase the supply of surface and groundwater, decrease sediment loads in dams and add nutrients to the soils.

Forest cutting activities held for centuries within the Ethiopian highland areas, particularly, cultivation of steep slopes and lack of erosion controlling methods on steep-farming- sites have all made it possible for the diminishing rates of the fertile cultivation land existing along the Abay Basin.

Due to the ever continued (a) protective vegetation cover loss, (b) the fertile topsoil disappears, (c) the increase in surface runoff and (d) the diminishing ground water because of impermeable soil for accumulating the rainwater, the farming activities are not functioning well. Consequently, abnormal floods and unexpected droughts keep on increasing within Ethiopia, which, in turn, can affect the farming conditions and the and human settlements in the lower riparian regions unless urgent cooperative measures are taken to prevent these unwanted incidences as quickly as possible.

In view of the fact that 80% of the land in Egypt is desert; and because there are only three more mouths to feed every minute due to its exponential (rapid) population growth, every drop of water and every kilogram of fine silt is important for Egypt’s survival. As Egyptians commonly say: “Nile is their life”. However, due to environmental deterioration and poor water management, the salinity conditions along its dams are increasing. The customary rise in the Nile’s ground water repeatedly causes salinity condition in the root zones mainly killing plants. These problems are also aggravated by arable land losses within the Nile region.

The need for partnership and mutual cooperation

Overall, land degradation, desertification, financial constraints and political instability are main causes of urgent concern for all three Basin countries (Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan) in the region.

As regards mutual utilization plan for the Nile Basin waters, although several agreements were signed in 1891, 1902, 1929, 1959, 1967 and 1991, none of these colonial agreements

agreement did not fully promote Ethiopian interests, or protect its natural resources/rights. Unfortunately, except serving as Declaration of Principles, there are no international laws on any of the river basins.

Neither the 1997 nor the 2014 UN Declaration of Principles is given the due respect that could lead to an understanding between water contributors and users. Interestingly enough, Egypt and the Sudan, which do not contribute to the well-being of the ABAY water resources within Ethiopia, are the users; while Ethiopia’s rights have been totally denied or given deaf-ear for quite a long while. Until recently, Ethiopia had only less than 200,000 ha of land put into irrigation farming system. Almost all irrigated farms are functioning outside the ABAY Basin areas within Ethiopia, whereas the irrigated farms in Egypt are estimated to cover more than 3.8 million hectares of land.

Obviously, for centuries that have gone by, Ethiopia has lost its regional and natural water resources use rights unable to divert the river waters for its own development purposes. Notwithstanding this reality, Egypt has continuously engaged itself in a permanent campaign to block any provision of grants and loans to Ethiopia in the intent to development projects on the Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin. Amidst these socio-political actions, Ethiopia, not only lacks adequate capital and modern technology, but also adequate hydrological data to carry out its ambition of utilizing the GERD for its hydro-electric power. In contrast, Egypt has already sophisticated hydraulic technology and river-basin information, that is backed by developed countries and international financial institutions.

What is happening today is that the lower Abay riparian states, particularly Egypt, are demanding more water volumes to flow down from Ethiopia without contributing to the rehabilitation of the deteriorated environment in the Abay Basin areas inside Ethiopia; nor do these states try to utilize other complimentary sources on a large-scale (such as renewable groundwater resources, an innovative water-purifying and drip-irrigation techniques as their neighbour – Israel does). As a chemistry professor, Adham Ramadan (2019), who specializes in water desalination suggests: “desalination is made more cost-effective, it could be used on a much wider-scale in fresh water production for use in agriculture and for the increase of human capital in new settlements”.

Instead of sharing the environmental rehabilitation costs by providing required and mutual support for the ongoing GERD-construction in Ethiopia; and benefit from the fruits of this plan, as always, Egypt continues to oppose this indispensable program.

According to the International Panel of Experts, the GERD-project will not reduce the amount of water that is flowing into Egypt and the Sudan. Rather this plan enables the two sister countries to develop more land via irrigation farming, as the GERD will properly regulate the water flow to the downstream areas.

If the physical and human environments of the region is well-realized, then, the GERD is carefully designed (which is already done) and maintained plus the water volume will be properly managed in order to provide sustainable ecosystem, food, feeds, nutrition and environmental security. It will also increase ground water and woody vegetations. What is needed now is understanding and making genuine tripartite cooperation among the three sister countries for equitable and legitimate water resources use.

Cooperation as a source of mutual benefits

Customarily, trans-boundary river basin water has often been often known as a source of international conflicts and ultimate war. In recent years however, trans-boundary water resources have become sources of regional cooperation and mutual resource sharing rather than opting for confrontation and costly war.

Examples of water utilization based on mutual agreement and cooperation include, among others, agreements concluded between: (1) Leseto and S. Africa, and (2) China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Although shared water resources in combination with water scarcity lead to political conflicts, these conflicts tend to result in the parties taking stock and finding ways of cooperating on this common resource.

International institutions such as: The African Union, IGAD, the European Union and the Arab League have all the obligation to stimulate the ideas of mutual cooperation so that trans-boundary water should become an important factor for bringing: (a) regional peace and stability, (b) food and nutrition security, plus, (c) environmental sustainability.

That means, at the end of the day, countries located along the Abay (Blue Nile) River Basin should mutually cooperate by sharing the benefits that may be derived from the use of water-led resources (such as: effective energy exploration, efficient farming and transport, as well as tourism industry).

Similarly, they should be obliged to help one another in sustaining food crops production, where it is climatically most advantageous and the produce is then traded. Such cooperation leads to an added value or a plus-sum game, where all parties can be on a win-win situation; instead of opting for a zero-sum game, where they could face a win-loss game situation, where the win of one becomes the loss of the other.

At this juncture, what should be mentioned is that, genuine cooperation should not be limited only to sharing the benefits but also express itself in sharing the costs incurred in the GERD-management processes. For instance, if water scarcity and resource-use conflict as well as political confrontation are to be eliminated or avoided, then, sharing costs incurred in alleviating the degraded environment is the most fundamental factor to prioritize for upcoming actions.

Even though mutual cooperation is considered essential, it cannot completely ameliorate trans-boundary water scarcity. That means, trans-boundary water scarcity can be created and alleviated through mutually managed and sustainable land utilization and water resources management strategies.

This requires understanding, trust and confidence among the upper and lower riparian countries. Through mutually agreed upon and sustainable water resource use, through genuine cooperation and determination to rehabilitate the deteriorated environment, the Nile, Baro-Akobo and other river basins in the region as a whole can provide sufficient and adequate water and soil nutrients plus food and nutrition security all year round for all three countries in the region.

Summary

At the moment, the demand for water use is increasing exponentially, while we are yet to fully understand the impacts exerted by physical and human environments on obtaining and maintaining water sources. Neither the international laws and regulations, nor the upper and the lower riparian states have established real understanding about the interplays existing between water sources and the environment they function with. There is crucial need to realize on how water resources use can either be utilized through conservation-based natural resources development or be misused through depletion of them. These phenomena are exposed in the following five scenarios:

Scenario 1: In recent years, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has been a point of disagreement between Egypt on the one hand, and Ethiopia and Sudan on the other. As an upper riparian state, Ethiopia may demand a heavy tax or export duty on the fresh water flowing from the Abay Basin and immense volume of fine silts, which are transported from its territory to the lower riparian countries. It may also demand some form of compensation because of delays caused by Egypt on the ongoing construction and operation activities of GERD. The three countries, however, have not yet reached an agreement on the process of filling and operating it in spite of years of negotiations.

These tensions between the three states are not new: The Nile has been a cause of antagonism between Ethiopia and Egypt for centuries. The Abay Basin, which flows from the Ethiopian highlands, contributes to more than eighty percent of the annual flow of the Nile (the remaining water coming from the White Nile, which flows from Lake Victoria, and Atbara /Tekeze/, which also flows from Ethiopia). The rich sedimentation that is carried by the seasonal flow of the Abay Basin (Blue Nile) has been the mainstay of Egyptian agriculture for millennia. And starting from the times of the pharaohs, Egyptians have been wary of an upstream dam that would strangle the flow of the Nile.

Scenario 2: The GERD, which is huge-enough to contain the main volume of water, most sediment loads will be deposited in the reservoirs. As a result, adequate and sufficient fine silts/soil nutrients/ and fresh water will be supplied on a regular basis to the lower riparian countries. As productive ecosystem and essential environmental security is going to be created in the ongoing GERD /artificial lake/. That means, all countries within the Abay Basin will benefit from this dam operations. However, key prerequisites for its success include, among others, peace in the region, cooperation, understanding the hydrology, hydrogeology, climate change-induced environment, socioeconomic conditions and financial inputs and moral support required from the international communities. In short, this well intentioned GERD will not negatively affect the water volume and fine silt flow. Rather, GERD can reduce sediment loads in the lower riparian countries, which are among the major problems consistently faced thus far.

Scenario 3: If present levels of environmental degradations continue, these in turn can lead the overall regional environment, both in the upper and lower riparian countries, to severe land degradation, drought, and causing further unexpected destructive floods, and low agricultural productivity; which all of these negative activities lead to mass popular migration, food insecurity/famine, and socio-political instability, human and animal mortality.

Scenario 4: Realization of the GERD can lead to both short- and long-term sustainable water resources utilization measures. If the upper and lower riparian countries are united and cooperative in the realization of the GERD program, then, this opportunity can alleviate any environmental threat, bring both water and fine silt sufficiency, and result in sustained food security in the region. The three sister countries must share the burden of managing the GERD and determine to rehabilitate the Abay Basin consistently in order to utilize its water resources for the common benefit of their respective population through conservation-based sustainable natural resource management policy governing the three countries. Such an understanding may lead to efficient use of water and energy and increase the agricultural output for both the upper and lower riparian countries.

Scenario 5: When completed, the GERD provides an artificial and beautiful lake scene, which are essential to run: the water cycle; reduce the floods effect and sediment loads; prevent landslides, soil erosion, desertification, drought and assure a high quality water supply and fine silts for farming purpose; provide productive ecosystem; clean and renewable energy and natural cooling system, which all has the ability to ameliorate climate change problems. The GERD can also be used as: a research centre; it can supply different fish species that can be raised in the regulated reservoir; people can swim and have other recreational activities; it can contribute food, feed, nutrition and environmental security, which are all indispensable to the upper and lower riparian countries.

Concluding remarks

Water has an environmental and ecosystem functions and plays a crucial productive role. The availability of water and water crises is not associated with the crises of the physical water availability but rather is poor environmental governance (deep-rooted power relations), extreme poverty and related inequalities. In order to improve the livelihoods of the present and coming generations in the three countries, we need to look at water as interlinked issues, such as supply, quality allocation, distribution and equity with respect to food and environmental security not by hostile acts against Ethiopia to stop it (which is impossible) from building environmentally friendly dams. If the upper and lower riparian states continue to argue over the so-called outdated “water rights” designed by the colonialists, more environmental deterioration is imminent. It is advisable to follow natural and societal/religious laws and use available water sustainably based on the ratification of the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework, respect, trust and equal opportunities in order to mark an end to the legacy of past hydrology-hegemonic aspiration. If the upper and lower riparian countries want to live in healthy physical and human environments, to increase life-supporting systems or to maintain healthy ecosystem function and have political stability and a sustainable future, environmental laws obliged them to live on sustainable basis.

The writer, Dr. Mengistu Woube is an Associate Professor of Agricultural and Environmental concerns. He has published several books and internationally recognized articles on diverse topics such as land-water resources management problems. He can be reached by E-mail at: biofoodp@gmail.com.

The Ethiopian Herald April 3/2020