Part I :- Book review

Kawase’s Mischief of the Gods is originally written in Japanese and translated to English by Jeffery Jhonson. In his epilogue Kawase states that his “book is an attempt to get closer, sing closer, and tell stories about the people I have met and interacted with in the streets of Gondar, Ethiopia and elsewhere.”

Kawase has really attempted to get closer and observe to come up with, I would say, several short story sketches in his book of memoir titled Mischief of the Gods. Every story has its own character, which is vivid, lively, and mind-blowing. Of all his acquaintances and friends while he was living at Gondar, Kawase chose the peculiar/distinct ones for his inclusion in his book of memoir. The Spirits of Piazza brings us three main characters: the flute boy/Balewashintu that’s nicknamed the Joker, the whistling teenager Gedamu, and the deaf showgirl Attu.

Each character brings forth some peculiar Ethiopian life style, belief, traditional and home remedial practices and the regular hustle and bustle with all its interpretations and implications.

For instance The Joker is a typical representative of flutists not only in Gonder but throughout the country who earn their living walking in town playing their flute and collecting tips to earn a living.

Gedamu, who is blind comes from the Semein Mountain and earns a living whistling. Gedamu whistles, putting his hand at his mouth and blows out a unique mysterious sound.

Kawase brings to light the commonly believed cause of the disease Mich, and the home remedy herbs Haragressa and Damakese.

“Mich metagn” or “I got struck by Mich” is a common term in Ethiopia used to describe illness caused by changes in weather or by eating certain foods, such as flaxseed and butter, especially when consumed in the sun. When someone is struck by Mich, they may experience symptoms such as chills or severe headaches. Additionally, if someone suffers from inflamed sores or blisters on their lips or mouth due to sunburn, this is also referred to as Mich.

A common home remedy for Mich involves drinking Damakese juice mixed with coffee. Sometimes, there is also a ritual performed by the person who prepares the coffee. During this ritual, the Damakese juice is squeezed by hand into the coffee cup. After drinking the coffee, the server—often a girl—keeps the residue from the Damakese leaves. She then holds the residue in her right hand and comes to the patient’s bed or seat. She rotates her hand over the head three times before taking the residue outside and disposing of it. It is believed that this ritual helps enhance the healing process by removing the bad omen associated with the illness.

In some regions of the country, it is also believed that conditions like blindness and skin discoloration (known as Lemtse) can result from being struck by Mich.

Coming back to Kawase’s Gedamu, “I heard from his cousin how Gedmu lost his vision: ‘After a long drought, it rained, steam rose from the earth and Gedamu was blinded by mich’ Mich is Amharic for disease caused by the sun. The common treatment is to drink medicinal tea made of plants such as Haragressa and Damakese.”

Attu is one of his subjects in the spirit of piazza, which has been described cleverly. Attu’s story is so captivating and unforgettable that it would remain in the minds of the readership for a long time if not forever.

“A woman known as Attu is a renowned character among the spirits of Piazza; she might best be called ‘Queen’. Her outlandish personality makes her stand out among the many spirits in and around the piazza. Prematurely aged Attu is also a deaf. She makes a living out of her movements: she stoops, lumbers in, and forcefully grabs the arms of passersby, revealing one of her drooping, wrinkled breasts and pantomimes breastfeeding a baby. She badgers people for money, making the claim that she has a baby to feed.”

Kawase details Attu’s everyday hustle dramatically. Residents of Gondar and other spirits of piazza know that Attu is faking it and she is a subject of ridicule as the urchins are mimicking her moves driving Attu crazy and leaving her crying loudly throwing stones/rocks at them and cursing the brats every day. However, Attu knows how to survive through her deceptive but naïve gesture until she disappears from the streets of Piazza. Reading her story and developing some sort of attachment to Attu, the readership would feel bad and get anxious as to what could have happened to her until Kawase found out that she was finally placed in a welfare facility that provides shelter and protection to disabled people.

The most interesting part of Attu’s story is what she did to the writer when he went to visit her at the facility with flowers in his hands. Attu has changed a lot to a better look, charm and odor. What her odor has been described as Atella /Residue of the traditional alcoholic beverage Tella/ when she was in the street is no more present and her outfit, hairstyle and general wellbeing was amazing.

“I offered her the flowers and she went to take them but hesitated looking confused and looking as if she didn’t know what the gesture was or meant. I gave her my blessing, said goodbye, and I was about to leave when she threw the flowers on the ground and grabbed me by the arm. Then she suddenly revealed one of her breasts and made a pose asking me for money. A great sense of relief spread over me.”

“In ‘You the Sun’s Lullaby,’ the author highlights the plight of street children in the town, labeling them as ‘Borko’ or ‘dirty pig,’ ‘Duriye’ or ‘rouge,’ ‘ruffian,’ ‘Godanna Tedadari’ or ‘child on the roadside,’ ‘Berenda Lijoch’ or ‘children under eaves,’ and ‘Adegegna Bozene’ or ‘probable dangerous criminals’. Kawase seeks to understand and document why these children end up on the streets. Some survive by vending, shoe shining, tour guiding, or running errands for Gonder’s residents. However, many remain homeless and marginalized.

One compelling story involves a boy trained as a pickpocket who, despite mastering his craft, experiences remorse after stealing from a woman. He returns the money, keeping only what he spent with excitement and consumed with guilt. Another notable character is Kangaroo, who despite his own homelessness builds a shelter for a stray kitten. Kawase empathizes with these children, delving into their psychological backgrounds, attributing their innate goodness, compassion, and repentance to their religious upbringing.

Mulu’s Snakes brings forth the tragic tale of Mulu, a beggar from the streets of Piazza. Like many street children, she frequents Kawase’s hotel room, where he welcomes everyone as a wise researcher. For Kawase, breathing life and understanding into his research requires embracing the human element.

“Mulu stands apart with her divinely pure demeanor among the street children and adults of Gondar. Upon entering Kawase’s room, she greets her host politely, then sits and picks up a pen to draw dots that eventually form into snakes. Her stories evoke memories from the writer’s childhood village.

Reflecting on his encounter with snakes as a child, Kawase recounts, ‘One day while playing in the river with friends, I spotted a pit viper coiled at the water’s edge. Foolishly motivated to show off, I seized it easily. In a moment of pride, a sharp numbness shot through the first joint of my right index finger.’ Unfortunately, Kawase fell ill and barely survived a near-death experience due to the snakebite, leaving his right index finger permanently bent.

The writer’s childhood adventure intertwined with Mulu’s story of snakes underscores the story’s essence. It poignantly reflects how serpents have appeared throughout the writer’s life.

As a character, Mulu meets a tragic end in a car accident—a heartrending conclusion to the tale of this innocent woman.”

Another vibrant character that Kawase introduces through his engaging encounters is China, the egg vendor. China got her name because of her small eyes which is a common nickname to boys/girls with small eyes. China has a traditional tatoo on her face in Amharic “Bale Nikkesat”, “Nikkise”, «Nikiseko” is a common name for village girls with tattoos on their faces. The author skillfully portrays the traditional method of tattooing, although the ingredients, tools, and techniques vary by region. According to Kawase’s experience, “The raw material for tattoo ink is soot from burning tires. This soot is dissolved in water and mixed with a liquid extracted from plant leaves to create a black ink-like substance.

BY ATA

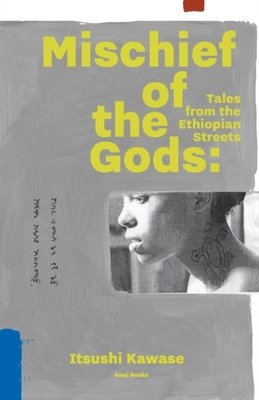

Title: Mischief of the Gods

Author: Itsushi Kawase /PhD

Publisher Awai Books

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD THURSDAY 17 OCTOBER 2024