In the first place, why should we read more African books, see more African movies, and listen to more African music? The answer to this question is not a difficult one. Simply put, the answer is that we are Africans, and we need to know our people and continent better than we know other places and other communities or societies. This answer begs the following question: why should we know our people and continent better? Here too, the answer is simple. As the popular adage goes, knowledge is power, and more knowledge of Africa by Africans gives them power in all its forms: economic, political, and social.

However simple and obvious the above questions and answers may look, the journey to knowing Africa and its people better than we do now has its challenges, often formidable due to the complex historical and contemporary context within which these issues are dealt with. To begin with, Africans have never been encouraged to know themselves, their cultures, traditions, philosophies, and thoughts simply because colonialism, that old foe, has prevented them from knowing themselves and forced them to know the colonial way of life, or a caricature of it, as their only alternative vision or knowledge.

Colonialism did not come to Africa only to occupy and control our natural resources although that was its ultimate objective. Colonialism first controlled the African mind and prepared it for accepting willingly, if not by force, colonial rule and colonial occupation. Occupation of the mind preceded territorial occupation. It sent missionaries from Europe to preach to them the doctrine of submission as if Africans had never had their belief systems and religions for thousands of years before the advent of foreign rule.

The missionaries, most of whom were disguised colonialists, came with the Bible to secure the submission and acceptance of European civilization by Africans who were deemed uncivilized, godless, and even savages. This dilemma was captured by Chinua Achebe, one of the luminaries of African literature, who exposed the prejudices of missionary conquest in Nigeria as it came into direct collision with local African traditions and belief systems. His novel “Things Fall Apart” thus became a universal literary sensation for its artistic exposure to this dilemma. The book was also popular in Europe because it exposed the prejudices inherent in the so-called civilizing mission of colonialism in Africa.

Without first occupying the African mind, colonialism could not have the subjective condition ready for its objective occupation of the continent. It was aware of the stiff resistance of Africans to foreign rule and more so to foreign occupation. Thus, it had to occupy the African mind before it occupied African resources and abundant raw materials. To be successful in this endeavor, European colonialism devised many tactics. Following its colonial conquests, Europe imposed on the continent European cultural practices and provided education to them that was specifically tailored to cement or consolidate its pernicious strategies of occupation and control.

African education was thus tailored to reflect European educational systems that subtly promoted the idea that since Africans could not educate themselves or develop their educational programs; they needed to be tutored by educated Europeans whose educational systems were the only ones feasible for Africans.

Education was thus used as a formidable tool for undermining African identities under a heap of European prejudices and Eurocentric biases. After independence in the 1960s, African leaders simply copied the European educational systems to govern their people the way the Europeans did by feeding them the same diets of cultural prejudices and superiority that were carefully cultivated under direct colonial rule. Africa was subsequently divided into Francophone and Anglophone Africa and African culture was reshaped accordingly.

The first generations of educated Africans were thus well-versed in British culture, literature and philosophy as they were educated in London and were shaped under the exclusive influence of British history, culture, and literature. Many of them were well-versed in Shakespearean drama and wrote their plays that were almost carbon copies of the British bard. Of course, Shakespeare’s literary influence was universal. Elsewhere in the world, his works were critically accepted while in Africa they were indirectly imposed on the educational system because Africans were considered illiterate when it came to culture and literature.

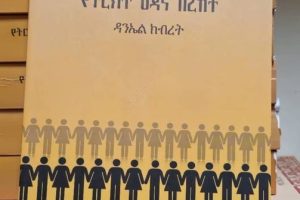

The fact that in the 7th century Axum in Ethiopia, people had the means of expressing themselves in their language derived from what was known as Ge’ez while Europeans still lived in caves. The civilizations that rose and fell in Egypt, and the African-Arab world in general had their own sets of written languages that expressed and reflected African traditions, cultures, and philosophies. In West and Southern Africa, too, little-known and original civilizations had appeared and disappeared while Europe secured its dominance and continuity by subjugating the people of Africa to its cultural and philosophical views that were anchored on the notion of African inferiority and European superiority.

The same paradigm was kept alive in Africa after independence and came to be known as neocolonial rule or colonialism by other means, mostly peaceful and deceptive. The entire cultural establishments in newly independent African countries continued to be dominated and controlled by the European models of education. Books written in Europe found ready markets in Africa as the educated elites popularized them and took them as models of artistic or literary excellence. Both in so-called, Francophone and Anglophone Africa, the newly emerging cultural elites adopted the respective traditions as their guiding lights in arts and literature.

It may not come as a surprise because the post-independence, as well as contemporary African elites, continue to be obsessed with European and Western arts and culture to the detriment of genuinely African traditions in literature and the arts in general. The question of why many Africans do not read books written by Africans, see films made by Africans, or listen to music invented by Africans is not a mystery. In brief, why Africans do not know how their African compatriots live and think is the dilemma behind their self-alienation and cultural suicide which is reflected in politics as a lack of genuine African unity, integration, and economic and social development.

Most educated Africans were brainwashed into thinking that Western literature, arts, movies, and music are the best in the world and that there was no point in trying to rediscover the lost souls of African culture because we have the best alternative for sale in the market. This is the way Western capitalism has produced and reproduced the culturally submissive generations of Africans who lack the boldness if not the confidence to try to resurrect the lost souls of African cultures that have already demonstrated their potential for growth as part and parcel of the global cultural heritage or patrimony. That is also why the notions of “Africa rising” or African renaissance” have lost much of their appeal. Africa cannot rise on the soil of Western achievements. Neither can it bring about its renaissance on the crumbs of the European renaissance that reflected European visions. Africa should therefore build its vision to achieve a genuine rise from darkness and a genuine renaissance based on Africa’s true soul or spirit.

This is not a call on Africans to abandon reading non-African books, stop watching Western movies, or listen to Western music. It is rather a call for African-educated elites to be more critical and more discerning in their approach to foreign cultures and arts. How many Africans know and appreciate our writers, filmmakers, and musicians? How many Africans are fans of Western movies and music?.

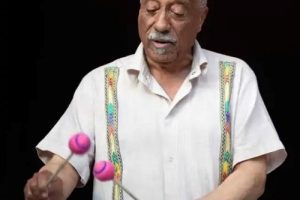

How many of Africans know that Mulatu Astatke is the father of Ethio-Jazz while most of us know that Michael Jackson was one of the richest pop singers in American history or that Jay Z is his contemporary equivalent? How many Africans know that Haile Gerima is one of the best African filmmakers who has consistently championed African freedom and the African culture he expressed or reflected in almost all his productions?

The new generations of educated Africans turn to Western culture because we seldom celebrate our uniqueness and defend it in the face of the irresistible Western cultural domination through the marketplace. This is the time to look horizontally to us and relate to one another on the lofty ideals of African unity, and African cultural liberation while taking anything positive and constructive from the wealth of global arts and culture. Through time, what is authentically African can emerge and promote our vision of a rising Africa whose renaissance would be based on its cultural resources and the hard work of its talented sons and daughters.

BY MULUGETA GUDETA

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD WEDNESDAY 19 JUNE 2024