Adult education in Ethiopia, otherwise known as literacy campaign, was, in the early days of the Ethiopian revolution of 1974, one of the key programs of the military administration whose leading objective was to give the rural and urban masses access to basic education centered on alphabetization. It was later on considered the key precondition for the economic development of the country. Since the time of the monarchy, education in Ethiopia was considered the engine of economic and social development.

Literacy, is defined as, “The ability to read and write at a designated level of proficiency. Literacy is more precisely defined as a technical capability to decode or reproduce written or printed signs, symbols, or letters combined into words. Traditionally, literacy has been closely associated with the alphabet and its role in written communication.”

According to Encarta Encyclopedia, “Literacy is not an inborn human characteristic, but rather an ability that is learned, most often in schools. No correlation has been found between literacy and intelligence, but literacy and educational level are closely related. Experts have long considered literacy an important contribution to the healthy development of individuals and societies.

Adult literacy programs can be distinguished by the stages of literacy they address. Programs to counter below-functional literacy stress the development of decoding and word recognition, similar to the goals of early elementary schools, but they use materials more appropriate to an adult age. Programs that deal with development at the functional literacy level stress the use of reading to learn new information and to perform job-related tasks. Advanced literacy programs stress the development of higher-level skills needed for high school equivalency diplomas.”

However, the adult literacy program under the Derg and in the context of the Revolution was designed as mobilization for the implementation of the Land Reform program that followed it. Critics of the regime however portrayed it as an attempt to neutralize opposition by sending tens of thousands of young high school and university students to the provinces in order to undermine their political activities.

The program was shaped after a similar program that was successful in Cuba in the early days of their revolution. “The great importance of reading ability is underscored by the growth of literacy programs in some Third World nations, as, for example, in Cuba. These programs, which generally send young people to rural areas to serve as teachers for illiterates in a national effort, often combine the teaching of reading with political instruction.”

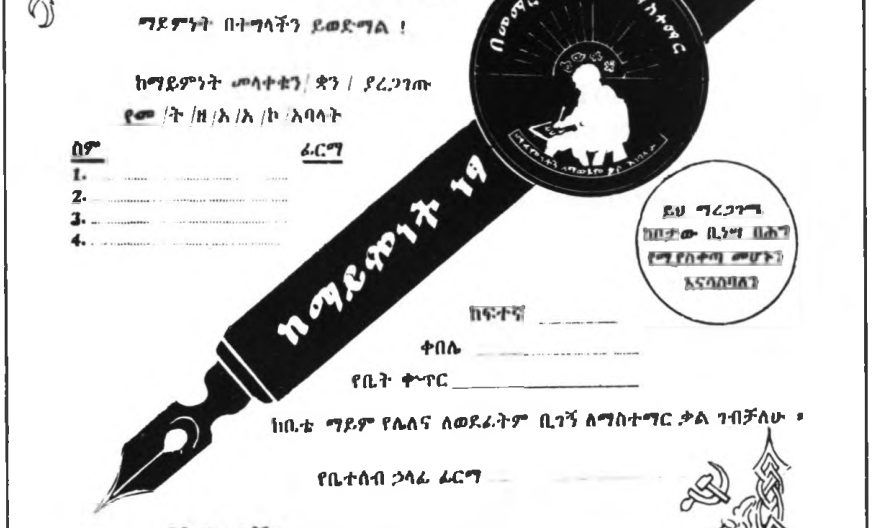

The launching of the Development Through Cooperation Campaign, otherwise known as the Zemecha back in 1976, was a massive mobilization of the educated youths of the country whose number exceeded 60,000, to take part in the first massive grassroots educational program. Its objective was ambitious indeed. In the long term, the program aimed at eradicating illiteracy from the country while its short-term ambition was to allow a great number of peasants to acquire the basic skills of writing and reading in order to expedite the land reform program.

The Zemecha was not however the first program of alphabetization. Under the previous imperial administration, there was an alphabetization program such as “ye’ fidel gebeya” literally meaning ‘the market of alphabets’. It was not however as massive and widespread program as the Zemacha initiative whose scope covered the entire country and all sections of society and involving almost all the nationalities of the country.

The alphabetization campaign aimed at educating 19 million people throughout the country back in 1978. But, as the literacy campaign and other development objectives of the Zemecha that were expected to take place could not materialize in the following two years. The social and economic disruptions that followed the Land Reform program created so much chaos and upheavals that cut the program short. Young campaigners in many provinces clashed with landowners in the name of “class struggle” that led to the early interruption of the entire program together with the literacy campaign that was so promising at the beginning. Nevertheless, successful initiatives were taken to continue the program under the supervision of a national institution and a well-planned program. In the final analysis, the program proved untenable in the long-run due to the fact that it was put under the leadership of political institutions rather than under civic organization. And when the political process met formidable challenges, the literacy program simply stumbled or went out of steam. With the end of the Derg regime, it altogether disappeared for good, leaving behind only hazy memories of its ambitious beginnings.

In the last thirty years or so, the adult literacy program has almost ceased to exist. True, the adult literacy program of the Derg had clear political connotations and it was used for mass mobilization in support of the government whose program had socialist tinge. By definition, “Adult literacy programs assist adults to become literate and obtain the knowledge and skills necessary for employment and self-sufficiency to allow parents or guardians to obtain the educational skills necessary to become full partners in the educational development of their children.”

While this program enjoyed considerable popular support at the beginning, it started to lose its momentum sooner than later. One reason was that the literacy campaign could not go beyond the objective of helping the population to read and write and do simple arithmetic. Once this objective was achieved, it could not proceed beyond it because the necessary preparations were not made to take it beyond its first phase.

True, millions of people had started to see the light of literacy for the first time in their lives. Older people in their 60s, 70s and even beyond went to attend literacy classes that were given at night as well as during the day, in the shadows of trees and in makeshift classes as well as in the rooms and premises of regular schools. Many people could sign on documents for the first time in their lives instead of putting their thumbs to ink and pressing them on papers and do simple arithmetical calculations as they did in the past. But all this effort went to waste soon after they graduated from literacy classes and stayed at home for lack of additional activities that could help them develop their skills further.

The post-literacy educational opportunity was totally absent as functional literacy was non-existent and those who graduated from literacy classes could not link their newly acquired skills to promote their practical activities and their job prospects. Millions of people who were made literate in a short time had no alternative other than reverting to illiteracy as they forgot how to use their new skills that they acquired with so much dedication and so much enthusiasm.

Although some attempts were made to save the situation by creating what where called then centers for training adults who have acquired the literacy skills, this too proved untenable as neither adequate preparations and technical and financial resources that could support the new program were lacking. As some analysts indicated at that time and what they called “campaign fatigue” or “campaign burnout was one of the hurdles that prevented the campaign from continuing with renewed figure.

According to a document released at the time of the launching of the literacy program in Ethiopia, “When Ethiopia launched its National Literacy Campaign (NLC) in 1979, it was announced that illiteracy would be removed from the urban areas of the country by 1982 and from rural Ethiopia by 1987. By the end of the twelfth round of the campaign, in February 1985, 16.9 million youths and adults had been covered by the NLC and 12 million of them. Almost half of them female had earned literacy certificates after passing a test. These impressive results do not mean however that the program had achieved its objective.”

This does not however mean that there was no improvement in the average literacy level of the country which was only 36.70% for a long time until 1994 while it has grown to 51.77% by 2017. There was also what was known as integrated functional adult education that was aimed at integrating basic literacy skills with livelihood of adults. This was also known as functional literacy. According to another information, “The Revolution of 1975 provided a springboard for further development especially in the areas of education and literacy. The literacy rate rose from 5% to the current 64%”

According to related information released in 2012, the adult literacy rate in Ethiopia has grown substantially. A breakdown of the literacy rate by region shows that “Addis Ababa Administrative Region was 93.8 percent, followed by Dire Dawa with 75.9% and Harar 71.2 percent. The lowest literacy rate was observed in Somali region with 30.5 %.”

No serious attempt has been made to continue the failed legacy of the Derg’s adult literacy program. However, such a program should have been dependant on the regime in power but on independent institutions or non-governmental organizations to ensure its continuity irrespective of the political system in place at a particular time. The now-defunct adult literacy program had started as a historic event and a positive initiative with the lofty objective of helping millions of people acquire the skills of writing and reading that could have served as bedrock of economic and social development. The vision was lofty indeed but the execution was sloppy and misguided.

BY MULUGETA GUDETA

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD FRIDAY 14 JUNE 2024