Who can deny the assertion that the best books were written in the 17 years during which time the Ethiopian revolution was kept either with bullets or the ballots, that is to say, real bullets and fake ballots? Who can deny the fact that some of the best pictures were painted, the best music composed, the poetry written during the revolution? Every living or dead Ethiopian youth of the time had books inside them. They had poems in their hearts and a hundred ideas for painting Some of them died without writing them while a few of them managed to write a few books that were sometimes controversial and even claimed their lives like Oromay by Bealu Girma.

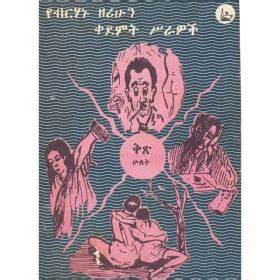

Author and journalist Berhanu Zerihun wrote a trilogy about the revolution and it became instant sensation when it was read over the radio and people had the opportunity to listen to their own stories. That was the time when the best Ethiopian writers and journalists were producing works that witnessed those momentous events for good or bad. There were writers who experimented with “Socialist realism” inspired by Russian authors like maxim Gorky, Mikhail Sholokhov, author of the epic “And Quiet Flows the Don” that won the Nobel Prize for literature. On the Ethiopian side, a journalist and writer called Tadele G/Hiwot published a short novel or novella entitled “Lekeyi Abeba”” (For the Red Flower) in the socialist realist style whose leading character is a proletarian.

The revolution has also inspired many short story writers who emerged from nowhere to share their experiences with their fellow writers and the reading public. There were very talented and young ones among them. The genre was almost unknown before that period when emerging writers had the opportunity to publish their books at the Ethiopian Book Centre, a private publishing house and Kuraz publishers that was owned by the state.

Poets like Debebe Seifu wrote their finest lines and published them in anthologies. Laureate Haddis Alemayehu published “Wonjelegnaw Dagna” (the Criminal Judge) and its was critical acclaimed although it did not surpass the popularity his previous work entitled “Fikir Eske Mekaber” (Love Unto Death) that is still considered the best and classic Amharic novel.

As a historical fact, what is known as the Ethiopian revolution is not something that can be ignored, overlooked or denied. That was one of the most important watersheds of modern Ethiopian history as important as any other event before it. It has deeply influenced not only the actors but also changed the economic, social and political life of the country for good. It was a chapter of our history whether we accept it or reject it, like it or abhor it. And it is now time to look back at it and get a more sober and more realistic retrospective overview of its pluses and minuses.

The older generation of Ethiopians, are this year, observing or better, remembering the 50th anniversary of what is known as the Revolution, an event of historical significance for many generations, an event of great importance both for its positive and negative impacts. The second and third generations that came after 1974 have “second hand” memories or versions of those events; gathered mostly from their parents and less from books. The books about the Revolution were mostly written subjectively or from the point of view of the parties that were hostile to one another and this hostility is still very much alive buried deep in the collective psyche.

The Revolution has shaped out consciousness and controlled our mind to such an extent that we are still unable to shake off the obsolete or mistaken ideas that led us to so many mistakes we are often unable or unwilling to admit. This has gone beyond politics and has impacted us as human beings by changing our characters, thinking, or opinions. Most members of the generation of 1874 are sometimes nostalgic or those days long gone.

Others are still living with their deeply buried psychological traumas and denying that the revolution has done nothing wrong but individuals have made mistakes. Still others are nostalgic of that period in their life because it coincided with their youth and with youth come romantic experiences and all kinds of adventures that never disappear from their memories. That is why revolution and youth are almost considered synonymous in the public imagination.

That may be why so many writers of that generation are now writing about it with love stories as the main plots of their narratives. Our opinions and “analyses” of that event are still unchanged despite the traumas and tribulations that generation endured until now while many have disappeared earlier without even getting the chance for a flashback. The less educated members of that generation are still looking at the post-1974 period as the “golden age” of cheap consumer goods, easy to build houses, a period of funs and fanfares.

They sometimes go as far as demarcating their lives as “before the revolution” and “after the revolution”. Anything that happened since then is bullshit for these people. They are entitled to their personal opinions. Such opinions often find currency in tough times like the present one when life is expensive and what we eat and drink and where we live is largely dependent on our monthly incomes that are not much to begin with.

The trouble is that we are not looking at the revolution in a fair and honest manner focusing on what it has denied us and what it has given us. The sad fact is that no writer or intellectual worthy of the name has so far tried to distance themselves from that time, look back and give us a dispassionate appraisal that would free us from our old and mistaken notions of partisanship and dogmatic outlook.

Now that all the actors and factors that shaped the revolution have almost gone, they should come out of their respective cocoons and stare at the truth in the eye and call a spade a spade. It is also sad that no one has so far dare say, “Yes! We were mistaken in this and that!” The so-called veterans of the revolution are still fixated on old and redundant issues of “who was right and who was wrong?” The funny thing is that the veterans of all colors have one color and that is red and they speak the same language that is Marxism-Leninism.

Personally, I have never read or listened to statements of mea culpa or self-criticism from the veterans who could stand apart and say, “Yes, we have made mistakes and also positive contributions!” What we are hearing is rather something like, “We have been always right to the very end!” Judging from the interviews they give and the speeches they make, most of the veterans of the revolution still sound narcissistic, nostalgic or beyond reproach. They are still fond of narrating their personal adventures instead of looking at those events with critical eyes and draw useful lessons if at all there are any lessons. That is why we do not have a definitive and all inclusive, balanced and honest history of the revolution. Unfortunately, we may have not produced intellectuals with enough talent, courage and integrity who could give us a definitive history of the revolution.

Nowadays, even the standard of scholarship is subject to criticism and talented scholars are not interested to touch the revolution as an important topic for book projects because it has always proved controversial and little known at the same time. It is a good thing that the media have started to mark the 50th anniversary of the revolution with discussions, presentations and interviews with the people who were present at that moment and members of the younger generation as well who are interested in that momentous event and how it affected their parents and siblings.

When it comes to the revolution’s impact on arts and literature, this should itself be a big subject of intense research and appreciation. When the revolution started in 1974, some of the most important Ethiopian painters were still alive and shared the enthusiasm and hope it had triggered. Afewerk Tekele was of course the greatest painter Ethiopia has offered the world. Although he supported the ideals of the revolution, without forgetting that he studied art in Russia, his background and attachment with the monarchy sometimes prove liabilities rather than assets for him. The radical elements were particularly vocal in criticizing him not for his paintings but for his personal ideas.

Probably the second and third most important artists of the same period were also Eskunder Bogossian and Gebrekristos Desta, both modernist painters who have departed from the traditional style as espoused by Afewerk. Gebregkristos was notable for also being a remarkable poet with his own poetic style and inspiration. Eskunder and Gebrekristos were abstract painters who introduced modernism in Ethiopian art although they did not produce younger adherents of modernism. Tadesse Mesfin was also an important and influential painter, born in 1953, and a young painter at the time of the revolution. His artistic career has span five decades and blossomed or matured through time. He has many followers and imitators and has taught many promising painters who later on assumed important place in the county’s artistic landscape.

BY MULUEGTA GUDETA

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD SATURDAY 9 MARCH 2024