BY MULUGETA GUDETA

Your bounty threatens me, Mandela, that taut Drumskin of your heart on which our millions Dance. I fear we latch, fat leeches On your veins.

Wole Soyinka “Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems, “Your Logic Frightens Me Mandela”

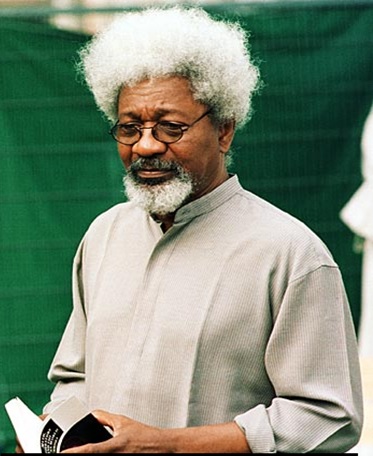

His energy is almost legendary. His commitment to the cause of Africa’s struggle against postcolonial oppression and exploitation is merciless. His criticism of the Nigerian post-colonial elites and their subservience to military dictatorships in his own country put him to the forefront of political activism. His courage is Herculean. He knew repression and exile under the military dictatorship of the late Nigerian president Sani Abacha who threatened him with death.

According to official sources, Wole Soyinka was born in 1934. He is a Nigerian playwright, poet, novelist, and lecturer, whose writings draw on African tradition and mythology while employing Western literary forms. In 1986 Soyinka became the first African writer and the first black writer to win the Nobel Prize in literature. It was only after Soyinka won the prize that the literary world has turned its attention to Africa. This in turn led to the emergence of prominent African writers who claimed the Nobel mantle. Mahfouz, Gordimer, Coetzee, Gurnah have followed on his footsteps. African literature has gained global recognition as a post-colonial creation that turned its focus against colonialism and neocolonialism, denouncing and exposing the very Western world that had inspired these writers.

Soyinka is a like a Yoruba warrior with pen in hand and an African who champions everything good about Africa and its people. He is celebrated by Africans and hated by the enemies of Africa. He speaks to his people, for his people and through his people, adopting their languages, dreaming their dreams, inheriting their imaginations and sharing their visions of freedom. He champions everything that is beautiful about Africa: its myths, legends, poems, conversations, dreams and myths. He is angry and horrified when tyranny strikes at the best and beautiful in Africa, like the killing of Ken Saro-Wiwa in 1995.

Ken Saro-Wiwa, Nigerian author and environmental activist, whose work aggressively satirized contemporary Nigerian culture and defended minority rights who said that “ The environment is man’s first right. Without a safe environment, man cannot exist to claim other rights, be they political, social, or economic.” and was killed by the Abacha regime. “ In 1994 the Nigerian government arrested Saro-Wiwa and eight others and charged them with the murder of four pro-government Ogoni activists. In November 1995, Saro-Wiwa and the others were executed, despite international protests from human rights organizations.”

Following the annulment of Nigeria’s 1993 democratic elections and the assumption of power by military dictator Sani Abacha, Soyinka went into exile in 1994. His subsequent essay collection Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis (1996) recounts the history of Nigeria from its independence from the United Kingdom in 1960 until the regime under Abacha. The essays show Soyinka’s anger and sadness over what he views as the deterioration of Nigeria as a nation. In 1997 Nigeria’s regime charged Soyinka with treason, claiming that he and other dissidents had been involved in a series of bombings. Soyinka denied the charges, and after Abacha’s death in June 1998, his successor, Abdulsalam Abubakar, dropped the charges. Soyinka returned to Nigeria for a visit later that year.

Soyinka often wrote about the need for individual freedom. His plays include A Dance of the Forests (1960), written to celebrate Nigeria’s independence in 1960; Kongi’s Harvest (1965), a political satire; Death and the King’s Horseman (1975); A Play of Giants (1984); From Zia, with Love (1992); The Beatification of Area Boy (1995); and King Baabu (2001), a satire about a fictional African despot. His other writings include the novels The Interpreters (1965), about a group of young Nigerian intellectuals, and Season of Anomy (1973); the poetry collections Idanre (1967) and Mandela’s Earth (1988); and the essay collection The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991). His principal critical work is Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976).

To say that Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka is the foremost African writer of the century would be an understatement. Soyinka is not only a novelist. He is a playwright and poet for which he won the Nobel Prize in 1993. He is also, a non-fiction writer, a political activist and perhaps the loudest voice of reason in Nigeria and Africa at least for the last 50 years.

This helps to explain the curious title of the first novel, The Interpreters. It is not about a class of clerical functionaries who mediate communication among people speaking different languages. It is about a group of young Nigerian professionals, “been-to’s” in the language of the 1960s, who have returned from studies in Europe to establish themselves in their newly independent country. Their fortunes are mixed, for various reasons: the corruption of the ruling elite places obstacles in their path at every turn, but equally, their personal challenges are far from straightforward.

And now right out of the blue, he has surprised us with yet another product of his fertile imagination and his inexhaustible energy. At 83, Soyinka is still writing, arguing, celebrating and championing the African and Nigerian cause that are one and the same. When he writes about Nigeria, it is as if he is addressing Africa and vice versa.

Soyinka published his new novel entitled; Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth” is published 48 years after the Interpreters which was published in 1965. According to Wikipedia, “The novel is set in the 1960s, in post-independence and pre-civil war Nigeria, mainly in Lagos. There are five main characters in the novel: the foreign ministry clerk Egbo, the university professor Bandele, the journalist Sagoe, the engineer turned sculptor Sekoni, and the artist Kola. They were friends at high school, then went abroad to study, and returned to start middle-class jobs in Nigeria.”

Stylistically, “The narrative of The Interpreters is seemingly chaotic, with Soyinka constantly returning to past events, and some effort is needed for the understanding of even the main characters, especially Egbo and Sagoe. Many other characters (university professors, editor board of the newspaper Sagoe is working in) are given schematically, fully conforming to the prevailing stereotypes of the era. This is because the novel was published in the 1960s, shortly after many of the African states became independent, and in fact Soyinka tried to build his narrative in order to oppose the stereotypes that were generally included in a post-colonial novel.” The structure of the narrative also ultimately forms a comment on the events that occur in the lives of several characters.”

Writing about Soyinka’s new novel, David Attwell, University of York, a lecturer and literary critic says that, “In part, Chronicles takes off from The Interpreters in following a group of young professionals, who meet as students in the UK, into late middle age and the height of their careers. Duyole Pitan-Payne is an engineer who dies in Salzburg on his way to a UN appointment; Kighare Menka is a surgeon known for his work on mutilated victims of Boko Haram; Prince Badetona is a statistician who walks a thin line between corporate finance and money laundering; and Teribogo, a university drop-out (he returns from his studies in righteous indignation, having been accused of rape) fakes his qualifications, drifts into the film industry and finally becomes an evangelist called Papa Davina, proselytising for a new religion he calls Chrislam.

In part, Chronicles takes off from The Interpreters in following a group of young professionals, who meet as students in the UK, into late middle age and the height of their careers. Duyole Pitan-Payne is an engineer who dies in Salzburg on his way to a UN appointment; Kighare Menka is a surgeon known for his work on mutilated victims of Boko Haram; Prince Badetona is a statistician who walks a thin line between corporate finance and money laundering; and Teribogo, a university drop-out (he returns from his studies in righteous indignation, having been accused of rape) fakes his qualifications, drifts into the film industry and finally becomes an evangelist called Papa Davina, proselytizing for a new religion he calls “Chrislam”.

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is satire, political thriller, and finally, in its darkest register, tragedy. It is the work of a great writer who is entitled to a deep sense of fulfillment, rootedness, and belonging; instead, in the words of Milan Kundera, he must feel as if his testament has been betrayed. The British newspaper The Spectators calls Wole Soyinka, “A towering figure in world literature, Wole Soyinka aims directly at the corridors of power as he warns against corruption both of high office and of the soul, with a dazzling lightness of touch and gleeful irreverence.

Praises are already being expressed by some of the contemporary novelists like who call Chronicles, “Soyinka’s greatest novel … No one else can write such a book’. According to The Spectator, “Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is at once a savagely witty whodunit, a scathing indictment of Nigeria›s political elite, and a provocative call to arms from one of the country›s most relentless political activists and an international literary giant.”

The Ethiopian Herald December 5/2021