BY MULUGETA GUDETA

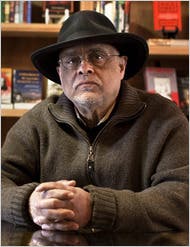

Haile Gerima is considered the best Ethiopian cinematographer who has made it in the Diaspora although he is little known here at home. He is a director, producer and script writer all in one not because he wanted to specialize in everything that involves movie making. He writes his own films because he has the talent to do so and writing comes naturally to him. He is a director and a producer because that is also the best thing he can do. What he has not so far achieved is the role of film distributor because that involves money and Haile is not the millionaire movie man we may imagine when we think of those in Hollywood.

Haile’s lifelong struggles in distributing his movies is recently the subject of a recent article entitled, “Haile Gerima On the Need For African Filmmakers to Reflect on a Continent That ‘Lost Its Mind’. The article is not specifically about the distribution of his films but about Haile’s trade mark criticism of African cinema, the role of African movie makers and his own critical remarks about Africa, that, in his opinion has “lost its mind”.

The article particularly focuses on Haile’s classic “Sankofa”, a film that first came out in 1993, and spoke to themes of “forgotten history and displacement.” Haile speaks of the difficulties involved in the distribution of “Sankofa” some twenty years ago. It is indicated in the article that “For Sankofa’s original release, Haile Gerima had to self-distribute and self-promote it with his co-producer and wife, Shirikiana Aina.

Now, thanks to ARRAY, the company founded by Ava DuVernay, the film will be made more accessible to a broader audience, notably by being accessible on Netflix in various countries around the world complete with an accompanying learning companion guide. It’s a far cry from the grassroots approach Haile Gerima and Aina had to take back in the early-90s when Sankofa struggled to find distribution and they had to, as Haile Gerima says, “foot-walk the film across 30/40 states for weeks.”

Commenting on the new release, Haile says that “It’s a very powerful way of bringing the film to people that are still searching, still trying to find it. Because we don’t even have a DVD of it,” This is considered a positive development something of a “restoration that has revived Haile Gerima’s spirits – especially in light of the disappointments and delays that come with being an independent filmmaker.

Haile sounds bitter about the negative effects of distribution delays create in the filmmaker when he says:”You make a film, and then you rest for ten years; you’re resting, literally – cinematically speaking. So that itself is a wear and tear of our experience.”

Yet, Haile GErima is not someone who can be discouraged by difficulties. He is rather past master in living up to the challenges and surviving under pressure. “It took Haile Gerima ten years to come up with Sankofa, on the back of his previous film, Ashes and Embers. Had it not been for the delays in the distribution of and recognition of Sankofa, Haile could have produced a dozen of new films so far given his high productivity and imagination in making serious films. His head may be bleeding but it is never unbowed. We can see this in the following remarks he made about the problem.

“The wear and tear is the problem for me because I’m also trying to empower my own cinematic narrative logic, and you get very fizzled in the process to get to practice your art. Because of the nature of cinema, and also the neglect of those films that are not part of the white supremacist kind of cultural industry. So you are facing all these things, and then the economic aspect of it and the technological changes. It’s very hard to keep up.”

Haile Gerima’s artistic survival in the struggle for making and distributing his films has close resemblance to his struggle to survive under an oppressive political climate. This shows in the themes he selects for his films. “The struggle to survive in oppressive political climates is a common through-line of Haile Gerima’s work. Ashes and Embers explored the disenchantment of returning African-American Vietnam War vets. His debut, Harvest: 3000 Years, dealt with an Ethiopian peasant family struggling to survive under feudalism and was produced in the midst of civil war following the overthrow of Haile Selassie’s imperial rule.

His most recent film, 2008’s Teza chronicled 30 years in the life of an Ethiopian man who lives through the country’s social and political crises. “That film is really speaking about how we got to where we are now,” he says. “This ethnic strife in Ethiopia is put in place in that period of the dogmatic generation that knew everything; the left-wing dogmatic generation with good intention but without education, without knowledge, without wisdom. This is where we are now.

Haile Gerima is also an outspoken, a controversial and militant filmmaker who thinks and works with contemporary Africa in mind while not neglecting his Ethiopian roots. Haile is a boy from Gondar whose father Haile Gerima was a patriot in the fight against Fascist occupation of Ethiopia. His father is also his main inspiration both as a man who inspired his courage and militancy against foreign powers that are dominating the cultural industry in the West that ignores Africa and African artists in spite of the fact that there were many talented movie makers among them in the past as well as at present.

Haile is also critical towards his African peers in the world of African cinema and does not mince his words when he says that, “Africans have lost their minds,” he says. “They have lost their historical context. They do not understand the resistance history of our own people; even when they were peasants and ordinary village people, they made history. And here we are, with all the airplanes we fly from place to place, with all the weapons we have to kill each other, we are still a continent of industry for weaponry, for destruction, guns and killing. We are the industry of disease. We are the industry of displacement and dehumanization, of human relationship.”

Haile Gerima is not only the most imaginative Ethiopian filmmaker but also a hard working man who is also writing new scripts that respond to historical events or history in the making. His film entitled “Adwa”, although he made it using stills and pictures to narrate the story of the great black struggle and victory against white colonialism.

He could have turned “Adwa” into an historical epic had one the richest Western film studios could back financially. However this could not materialize or will not materialize because “Adwa” is the shame of the white supremacists Western powers who fought against Ethiopia and black independence. But this not deter Haile from writing critical films that reflect his critical spirit and his vision of a new cinema world where African cinema could achieve its independence by overcoming its financial and political constraints.

Haile Gerima has the script for a film that he believes speaks to this — not only to the situation in Ethiopia but in Zimbabwe and South Africa too. “It’s called Independent Road, but I don’t think I’ll ever make it. I wrote it in Zambia and got the first germinating idea in Zimbabwe,” he says. “So there are films that I want to do where I’m trying to respond to the time. But I’m not the grandson of Kodak and my wife’s not the granddaughter of Sony Pictures or something. We have scripts to respond to the time we live in. Not only me but many filmmakers. We read each other’s scripts but they never get transformed into cinema.”

Haile is critical of what he calls “the white supremacist cultural industry” that is dominating global culture. He is also bitter against the African elites that have failed to provide the necessary support for Africa’s cultural revival. He says that, “The elite in Africa is deformed. It is created to serve a purpose, a higher purpose, for those who need the mineral resources for their cell phone planet, for the spaceship, etc. And we have an elite that is completely subjugated, and benefiting in that subjugation and creating its own fascist class.”

Haile Gerima is himself a displaced artist who speaks against Africans’ displacement and rootless existence away from their identity and culture. In this sense he is a militant pan-Africanist and anti-colonial artist who speaks for millions of Africans who have lost their cultural possessions and are kept in neocolonial spiritual bondage. His inspiration as an artist came from such prominent African artists like Osman Senbene and others who remained true to their African visions and made films that survived them.

However Haile’s pain and regret is transparent through his remarks about African film makers of the previous generation who toiled to the end without however bringing their works to fruition due to the overwhelming challenges they faced in their times. The lack of financial support to make these films is a tremendous source of despondency for Haile Gerima. “Med Hondo, Sembene Ousaman, they died with scripts still on their desk of their office,” he says. “There’s a sister called Safi Faye from Senegal; she’s neglected, there’s no money for her.” Haile Gerima sees the glory of being acclaimed as a director of little effect when the money to make further films does not accompany it. “I don’t want to go to beg Europe or America for African cinema,” he says.

The Ethiopian Herald October 14/2021