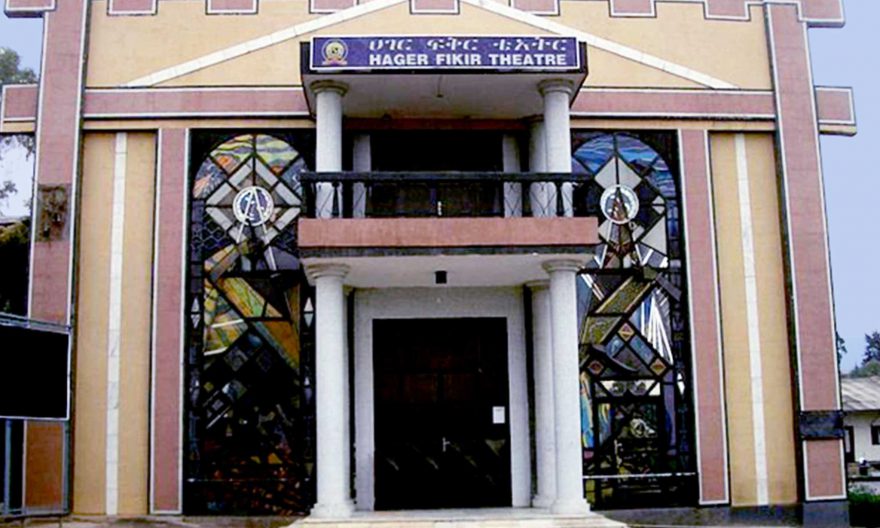

A brief description of the Hager Fikir Theater in Addis Ababa by Wikipedia says the following, “it is not only the theater with the greatest tradition in Ethiopia but also the oldest indigenous theater in Africa. The theater was founded in 1935 and it replaced a former night club.

“Later the entrance of the theater was rebuilt so as to resemble a real theater. Standing for more than 70 years of cultural life in Addis Ababa, the theater is a playhouse where modern Ethiopian music and drama were born and nurtured. Many stars like Aster Aweke, Tilahun Gessesse and Frew Hailu began their careers on the stage of Hager Fikir Theater. Both traditional Ethiopian plays and translations of European playwrights by William Shakespeare, Friedrich Schiller, Henrik Ibsen and Molière have been produced at Hager Fikir Theater in recent decades.”

This passage from Wikipedia has nevertheless omitted acrucial information about the role the theatre house played during the 1936 fascist Italian invasion as a place where patriotic playwrights used it to stage plays that mobilized the public against the invaders.

Nationalism and patriotism are not alien to Ethiopian playwrights like Tsegaye Gebre Medehin is not only the most important epic poet of Ethiopia. He is also the most patriotic or nationalist Ethiopian playwright whose works sing the praises of his motherland and the past glories of its people. Tsegaye used much of Greek mythology in his poems and plays to describe Ethiopia’s mythical existence as the origin of humanity and the beholder of original civilization at a time when Europeans lived in caves and America was not yet invented.

When the late poet laureate Tsegaye Gebre Medhin staged his play entitled “Hahu besidist wer” (ABCD in six months) back in the early 19700s, Ethiopia was caught in a revolutionary turmoil. The old regime had left the political scene. New political forces were claiming the political space and the entire country were filled with expectations of better times to come. The situation was akin to the 1789 French Revolution. The masses were out in the streets claiming their long-suppressed rights and freedoms. And writers like Tesegaye had a rare opportunity to prove themselves as conscience of the nation.

The revolutionary plays like “hahu besidist wer”and others like “enat alem tenu” (an adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage) had caught the imagination of the public that had never witnessed a revolutionary ferment that was threatening to engulf everything and everyone in its wake. Theatre was fast becoming the most effective medium for articulating the public fears and hopes and what was to be done to bring about the much-anticipated national renaissance that had eluded many generations before.

Ethiopia had never run out of literary or poetic prophesies. The problem was that the ruling powers never listened to the councils of the wisest men in town. Tsegaye’s plays enjoyed popular acclaim but the ruling classes ignored them at the cost of their own survival and the success of the revolution. In Shakespearean England, the theatre was used to criticize the madness and brutality, the cunning as well as the love affairs of the ruling classes. Henry V is one of Shakespeare’s epic plays that glorified British nationalism and heroism in the war against the French in 1599.

Tsegaye was a ‘Shakespearean’ playwright who was trained at the Royal Academy of Arts in London before he returned to his country to look at the Ethiopian realities with Shakespearean eyes. He translated some of Shakespeare’s masterpieces into Amharic and staged them at the then Haile Sellassie Theatre to great public and official acclaim. Like Shakespeare, Tsegaye too was not in good terms with the Ethiopian royal family and the aristocracy about which he spoke little favorable words and much more criticism.

However, he respected the institutions of royalty and worked within that framework. His devotion to Ethiopian unity and social justice was evident in his plays. He had no place for mediocrity and worked hard to make words become as expressive as possible, reflecting the deep passions of his characters who are out in the world to achieve something great, in love, in war as well as in patriotism. Suffice it to look at his play, “Petros yachin se’at” or Petros that Hour in which the main hero who is the high priest of the time sacrifices his life for the survival of Ethiopian freedom independence contemptuous to the fascists attempt to win him over.

When the military Derg stepped in to fill the vacuum left by the ancient regime things developed very fast; so fast that even prolific playwrights like Tesgaye could not catch up with events and things started to go wrong. The authorities managed the revolutionary crisis in ways that fitted their interests whereas the nation was being threatened with existential issues.

Back in the early 1930 when Ethiopian theatre barely existed and the first theatre house was opened as the Hager Fikir Theatre, the playwrights used the medium of the stage for spreading patriotism and resistance to the evil of fascist invasion and succeeded gloriously. Since its very inception, the theatre in Ethiopia defended the national cause against all the odds.

Fast forward to the 1970s and the political turmoil that was quelled quickly as a result of the acts of repression against new ideas and artistic productions, the Ethiopian theatre started to abandon its lofty mission of serving as the voice of the voiceless masses and sank into some kind of mediocrity from which it has not yet recovered.

Tsegaye was not only Ethiopia’s preeminent epic poet. He was also the voice of reason when political arbitrariness was dominant and the country finally descended into chaos. There were also the likes of Maniazewal Endeshaw and Getachew Debalke who shaped the modern Ethiopian theatre as directors, actors and producers.

No remarkable events happened in the Ethiopian theatre world during the last thirty years as far as new productions; new themes and new drama techniques are concerned. Ethiopian theatre witnessed some isolate successes while the overall situation remained unchanged. From the lofty and epic dimensions into which Ethiopian dramatic works had found their niches, they descended into mediocrity whereby the daily stupidities of life found prominent expression in works of comic or farcical laughter while the great themes of national unity, patriotic glories and humane achievements were pushed to the background and almost forgotten.

Tsegaye’s and his likeminded playwrights had set the bar of excellence too high so that no one could even remotely approach their talents. True there was a proliferation of radio and television dramas in the 1980s and 1990s and down to these days. However they were mostly hotchpotch works intended to amuse the audience as cheap entertainment pieces and earn their authors cheap popularity that faded as soon as the plays terminated their stage lives.

The last emperor and the aristocracy were relatively more enlightened in terms of arts and literature than the military and separatist henchmen that followed their rule. Ethiopian patriotism, national unity and the heroism of Ethiopians in the face of foreign invasions have always remained a central to the epic period of Ethiopian theatre. What followed from it however was a far cry from the previous era of artistic and literary excellence with so many epic poets occupying the creative space. And when commercialism invaded the theatre world, it attracted a few bees and numerous flies.

In the time of Tsegaye and his creative comrades, theatre was a much more respected and even venerated creative enterprise. In the last three decades or so it has turned into a caricature or a shadow of its old self. The so-called new generation of playwrights had nothing better to offer than occasional plays whose main objective is to make the audience laugh at the stupid acts and words of the actors. Hence, crass comedy took the place of lofty tragedy.

Ethiopia at present is at a critical juncture in its modern history. The forces of separatism, blind hatred and jingoism are threatening to tear apart the national cohesion and common aspirations of the Ethiopian people that was built over centuries of sacrifice hard work, love of motherland and commitment to Ethiopia’s past glories.

Ethiopian or African history witnesses the fact that a nation can achieve legitimate existence as a respected member of the international community when its constituent parts are guided by or aspire for a common vision. Separatism is the source of much of the trouble African nations have been facing since they gained independence in the 1960s. Civil wars have claimed many lives and led to the destruction of properties and turned the dreams of millions of Africans into nightmares.

Separatism is a cancer that eats at the fabric of a national polity and eventually leads to collective disaster unless it is curbed in time. The task of denouncing or preventing this from happening obviously falls on the shoulders of the existing few patriotic playwrights in the molds of Tsegaye, If there are any. Artists are pledging to go to the fronts to defend the country’s integrity. Their other roles should be fought on the stages of theatre houses. One can only remember the saying that the “The Pen is mightier that the sword”.

BY MULUGETA GUDETA

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD SEPTEMBER 7/ 2021