BY STAFF REPORTER

Pastoralists and agro-pastoralists are one of the most climate-change-vulnerable groups on the planet. It is necessary to increase their resilience to protect their livelihoods in the short term. Increased climate variability could decrease herd sizes as a result of increased mortality and poorer reproductive performance of the animals. This decrease in animal numbers would affect food security and would compromise the sole dependence of pastoralists on livestock and their products, as well as the additional benefits they confer. Under increased climate variability, the need for diversification of income, a strategy often (and increasingly) employed in pastoral areas, becomes ever more important.

The “Green Economy” is a vision of a future where greater material wealth does not increase environmental risk, ecological scarcity or social disparity. Moving towards a Green Economy requires growth in production and consumption without continuing to jeopardise natural capital and social equity. As economies and populations grow, so does the demand for animal products, including milk, meat and fibre.

Pastoralism can play a significant role in fulfilling this demand whilst continuing to protect rangeland biodiversity and ecosystem services. Many countries possess large areas of rangelands that are managed through pastoralism and which already make a major contribution to environmental sustainability as well as the agrarian economy. However, the environmental role of pastoralism is often ignored and is undermined by unsuitable policies and investments. With better policies and fewer disincentives governments can enable pastoral development whilst protecting rangeland environmental services that benefit the whole society.

Pastoralism is rarely viewed as a major future form of land use, because of well-documented cases of rangeland degradation, attributed to irrational overstocking by pastoralists, and the subsequent losses of ecosystem services. However, pastoralists were actually encouraged to settle and adopt such strategies, copied from rangelands with higher and more reliable rainfall. This curtailed mobility resulted in a shift from opportunistic and extensive land use to more intensive and settled forms of use.

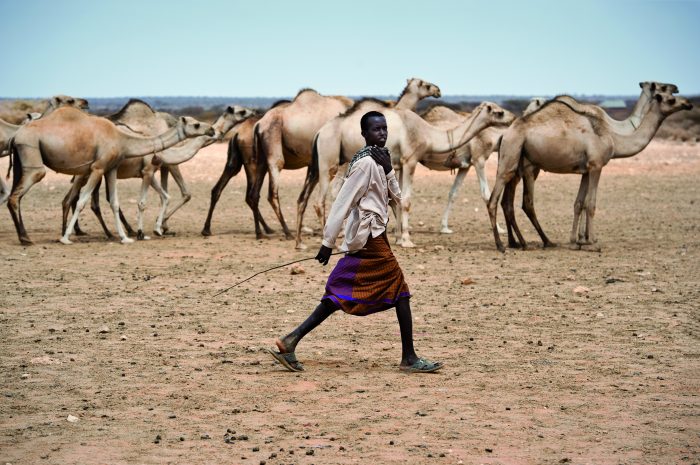

Pastoralists safeguard natural capital in more than a quarter of the world’s land area. Pastoralism is both a livestock management system and a way of life that provides globally important ecosystem services, which are enjoyed far beyond the boundaries of the rangelands. Herd mobility is central to sustainable pastoralism and can be practiced at different scales depending on local conditions: from short-term localised movements to long-range seasonal migrations.

The Livestock play an important role in carbon sequestration through improved pasture and rangeland management. Good grassland management includes managed grazing within equilibrium and non-equilibrium systems and requires: a) understanding of how to use grazing to stimulate grasses for vigorous growth and healthy root systems; b) using the grazing process to feed livestock and soil biota- through maintaining soil cover (plants and litter) and managing plant species composition to maintain feed quality; and c) providing adequate rest from grazing without over resting the plants (Jones 2006) and d) understanding impacts of and adapting to climate change, e.g. plant community changes. Grassland productivity is dependent on the mobility of livestock.

Investing in adapting pastoralist and agro-pastoral systems to future climate change is essential. This requires an appreciation of the fact that we need to start taking action now in order to have the right systems in place by the time the impacts of climate change are felt. This has implications for the strategic allocation of resources and the development of institutions and technology that will help effect these changes. There is a need to increase investments in infrastructure, particularly roads, as they ensure the connectedness of pastoralist communities and foster their integration into markets and into the wider economy. At the same time, livestock product market chains and food systems will need to be developed along with appropriate support systems, so that all consumers have equitable access to safe, cheap food locally. Technology will play a significant role in adapting pastoral and agro-pastoral systems to climate change, by, for example, helping to improve methods for harvesting water and sourcing feed, facilitating the substitution of species (i.e. from cows to camels) and enabling the production of different breeds to cope with different environments or disease burdens.

New alternatives to diversify incomes may be essential in some agro-pastoralist systems. Below, the authors review these issues and offer examples of adaptation successes. They conclude with a brief description of the research that is needed to advance and integrate the short- and long-term climate adaptation agenda into a coherent social development agenda in pastoral regions.

The impacts on grazing systems include changes in herbage growth (brought about by changes in atmospheric CO2 concentrations and rainfall and temperature regimes) and changes in the composition of pastures and in herbage quality. In higher latitudes, future increases in precipitation may not compensate for the declines in forage quality that accompany projected temperature increases, and cattle will experience greater nutritional stress in the future.

Increases in CO2 concentrations and precipitation will tend to increase rangeland net primary production, though this increase in production will be modified, positively or negatively, by increased temperatures. At least to the 2050s, increases in CO2 will benefit C3 pasture species, although warmer temperatures and drier conditions will tend to favour C4 pasture species. The proportion of browse in rangelands may increase in combination with more competition if dry spells are more frequent.

In a future East Africa with a warmer, wetter climate, for example, C4 grass productivity may decrease, while tropical broadleaf growth may increase. In such regions, decreasing grass cover would likely result in more competition for forage amongst grazing species. Changes in net primary productivity in African and Australian rangelands are likely to be largely negative (9). Projections into the future generally indicate widespread negative impacts on forage quality.

The results of global integrated assessments addressing the effects of climate change on land use, economics and changes in the productivity of the livestock, agriculture and forestry sectors suggest a variety of different impacts. They range from modest but beneficial impacts on rangeland systems, especially under CO2 fertilization effects and in colder regions, to detrimental impacts that reduce pastoralism’s contribution to household income and oblige pastoralists to transition to other types of more diversified production systems to maintain livestock productivity.

Greater recognition and support is needed for sustainable pastoral and agropastoral systems in view of their contributions to climate change adaptation and mitigation, disaster risk management and sustainable agriculture and rural development. Targeted support by governments, civil society organizations, development agencies and donors to communities, (agro)-pastoral networks, development practitioners and researchers is needed to provide incentives.

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD JULY 21/2021