Imagine one day Africa emerging as a united and proud country as one of the global economic powerhouses on equal footing with the giants of our time, like China or to some extent like Russia. Is this utopia? No, because China, which was a relatively poor country back in 1948, has now become the second largest economy in the world. Its culture is thriving and its impact on world affairs has been boosted. So, the possibility of Africa emerging as a united and one of the most powerful countries in the world is far from being utopian. It is realistic and possible.

Imagining Africa as a single country first took roots in the fertile minds of the early founding fathers of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president was the mastermind of this idea as he defended the unity of Africa at any cost without waiting more time for preparation or its realization. This idea was so revolutionary in its time that the debate was divided into two main camps. There were of course detractors and supporters of the idea of African unity both within and outside the country.

In the 1960s, colonialism was weakened but not completely overcome. Among the political elites within the continent, there were many who were not happy with the prospect for an immediate unity of the continent under one government. They argued that Africa was not ready at that time for continental unity. According to them, Africa was just emerging out of colonial rule and its economies and political structures were so weak that any idea of immediate unity could be disastrous.

They maintained that Africa should first overcome its challenges that emanated from hundreds of years of colonial oppression and exploitation. They said Africa needed the support of the former colonizers to channel the funds and resources badly needed for the reconstruction of the continent. In the final analysis, this idea gained popularity among the new African leaders whose interests were closely allied with those of the former colonizers. And the voice of the radical group like that of Nkrumah within the newly emerging Africa was stifled and nipped in the bud by the more conservative and pro-Western faction had the upper hand.

The division between those who defended Nkrumah and called for the immediate unity of African unity and those who said that Africa should unity in the long run or step by step ran deep. The main task at hand for the second group was the consolidation of each and every African nation in order to defend their sovereignty and independence against the prospects of possible second colonial conquest. In the final analysis, the advocates of “African unity now”, were in the minority and those who called for Africa to continue in its fragmented state by maintaining its colonial borders won the day.

From the perspective of present events, it would be hard to say this or that group was right in the decision they took 70 years back. If there is something undeniable in all this, it is the fact that Africa’s continuity as a group of 54 countries has not been a shining example of economic or social development. Colonialism was replaced with neocolonialism as Nkrumah warned in one of his books. Africa’s economic, social and cultural integration was not a total failure even if it failed to live up to the expectations.

Africa’s slow and painful development in the last 70 years was undeniable but it did not produce the expected results. Africa is still a continent where poverty and general backwardness are the dominant features. The continent has not even managed to protect its peace and tranquility and conflicts have become permanent features in the lives of its people. All these negative features are taken for granted these days and no serious intellectual has lost the appetite to discuss these issues. Africa has become a continent of people who resigned to their fate and waiting for miracle to happen in order to make life easier and more interesting.

Unfortunately, the debate around Africa’s future ware now ignored or simply overlooked for the last 70 years or so, and much water has flowed under the bridge since then. Looking back at the debates from the point of view of the present, we may conclude that Africa is not yet ready to become one country and the proposal of the early founding fathers of the OAU still remains only a big and lofty dream. But how long will Africa survive on meager staples of beautiful dreams such as “Africa Rising”, “African Renaissance” or Africa coming out from the cold? Fortunately, these questions do not prevent us from thinking about or asking the following critical question: Is it feasible to think or ask, at least theoretically, whether a united Africa could have been a bane or a boon to the survival of the continent? As we have no tangible experience to base our viewpoints on this question, it would be highly speculative and hence subjective to dream about a united Africa because it still remains nothing but a big dream.

Dreaming Africa as a single country with a population of more than one billion people, almost equal to that of China, may be attractive. The sad fact is that it always remains a dream and no continent is built on empty dreams. This remains an illusion at best until the time when we start to build enough consensuses and rise to make Africa’s unity a living and breathing reality. We may perhaps ask at this point what would Africa’s global economic impact in the world look like if it could muster efforts to integrate its economy tomorrow or any other day.

It only takes a small effort to calculate the aggregate GDPs of all African countries in order to see how the continent is faring in terms of aggregate growth. Then it would be easier to calculate the average per capita income of every African by dividing the total GDP by the population size. The problem is that it would be futile to go into these calculations because they reflect not the reality on the ground and remain largely speculations.

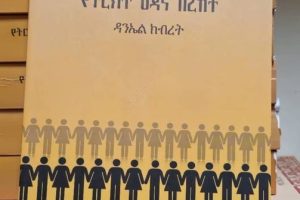

What would Africa look like had it been culturally integrated? This may be an interesting question because the answer would be interesting. Even in its presently fragmented state, Arica remains a continent of baffling linguistic and cultural diversity. It looks like a broad and beautiful tapestry of rich traditions, rituals, songs, dances, architectures, dressing codes and designs. Add to this, tens of thousands of stolen African cultural artifacts that are still languishing in European and American museums.

The repatriation of these artifacts would indeed add to the beauty and diversity of African cultural heritages unparalleled in the world. African countries have more or less lost various historical and cultural relics that are now found in various European capitals some of which are still regarded as war trophies or war booties. We need to reclaim what was ours and let the old colonial wound heal and the ongoing legal and illegal business with looted Africans treasures that is promoted with the full knowledge and sometimes the direct or indirect cooperation from European authorities although they are denying that such activities are taking place in their own turfs. That is why the repatriation of African cultural relics is increasingly assuming unprecedented importance. No doubt, that a united Africa could have accelerated this process because efforts at repatriation would be conducted in a more organized centralized manner with knowledge and information sharing at the national level. That would also add to the weight and prestige of African voices in international forums. This is perhaps the reason that makes Africa’s cultural integration such an interesting idea and not a lost cause

BY MULUGETA GUDETA

THE ETHIOPIAN HERALD SATURDAY 14 SEPTEMBER 2024